My grandparents were migrant farm workers, cherry pickers and hops harvesters. Though both were born in Texas, their Mexican identity and socioeconomic status determined their day-to-day lives, but not their future.

I’ve come to realize there is an unspoken pride in our family that is rooted in the Latine experience of the American Dream. My grandparents knew education was the pathway out of low wages and difficult working conditions, hence why my grandfather decided to work as a janitor at a public school to land a steady job.

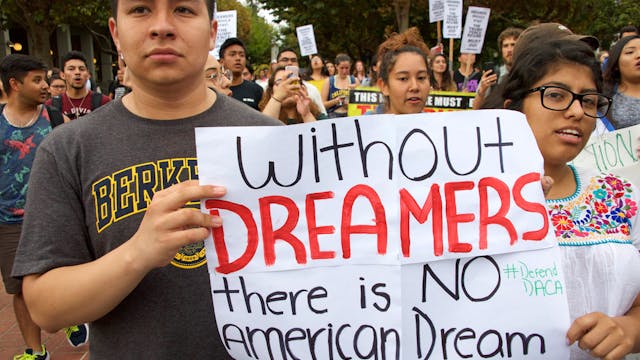

It’s no coincidence, then, that I am an educator and, as such, I think about how to present and process the American Dream with my students. When we think of the American Dream, we often conjure images of “The Great Gatsby” and Ellis Island but are less likely to unpack the image of the American Dream at the U.S. border with Mexico. From that dividing line, the American Dream guarantees safety, education, economic stability and outright survival for many Mexican and Central American people.

As a Spanish teacher, I have the opportunity to widen students’ perception of the American Dream to include the experiences of Latin Americans coming to and living in the United States. Even though I work at a small, all-girls Catholic school in Minnesota, we have students whose families emigrated to the U.S., and they’ve experienced the pain of an undocumented family member’s deportation, too. To them, the opportunities and challenges implied by the American Dream have never felt more real.

As the number of Latine students increases in my school, it’s important that we humanize the migrant experience so that we can redefine the American Dream for students today.

Living in a Bubble

Most students at our all-girls Catholic school believe they live in a bubble. While our school continues to become more ethnically and racially diverse, there is still this sense of being sheltered here, and that our school does not offer a true reflection of the outside world. This student's perception is slightly exaggerated, but I get it. Students want to be connected, cultured and aware of the realities beyond the classroom.

I also advise our co-curricular group, the Students of Color Society. The small group is led by two Latina students whose families’ stories, like my own, are bound to the promises embedded in the American Dream. These students and their parents believe in the power of education for their collective futures in this country.

I want to help students in my Spanish classes gain an awareness of that experience and get beyond their bubble. For me, a Spanish course is more than grammar structures; it is about connection, cultural competency and global engagement. I teach Spanish through a lens of history and justice because, for our students, it’s mind-opening to study Latin America and gain an understanding of its people. Students can then challenge the negative stereotypes of Latine migrants and the biased political campaigns they are exposed to in the media. This is how we start to puncture that bubble that will help our students hope to break free.

Redefining the American Dream

In class, we learn that Mexico, Central America and South America each struggle socially and economically. Because of this, many people and families migrate to the border, manifesting their hope to live violence-free, acquire secure employment and receive an education for the success of future generations. While dreams allow us to imagine opportunities that are within our reach, it is also important that as a class we study the various obstacles that inhibit the progress of historically and systematically marginalized peoples.

In order to humanize and create a deeper compassion for those who come to our border undocumented, we read the prologue and first two chapters of “Enrique’s Journey,” published in 2006 by Pulitzer Prize-winning author Sonia Nazario. Like our students, Enrique is a teenager facing unique life circumstances, but he lives in the midst of gang violence and poverty and suffers from depression and drug addiction, leading him to eventually drop out of school. His dream is to reunite with his mother who migrated to the U.S. in search of a way to earn a sustainable income for Enrique and his sister. Enrique navigates his journey to the Texas-Mexico border on the tops of trains and finds his mother, Lourdes, in North Carolina; yet, he discovers that living in the U.S. means exchanging one form of poverty and oppression for another. The American Dream, in reality, was paved with racial prejudice and limited low-income jobs that allowed Lourdes to barely make ends meet.

Reading Enrique’s Journey allows students to see a three-dimensional portrait of the migrant experience, and strengthen their muscles for compassion. Together, we discover how difficult it actually is to achieve all that the American Dream leads us to believe is possible.

From there, I ask the students to decide whether the American Dream actually exists for undocumented individuals. They often say no, or if it does, it is the exception rather than the rule. Without fail, students point out that there is one aspect of the American Dream that seems to lead to change and the future envisioned: an education for migrant families and children, but also an education for teachers and students like us who help shift the narrative on migration.

Education and Empowerment

During our school's annual celebration of Hispanic Heritage Month last October, the Latina leaders of our Students of Color Society shared their stories with our wider school community. They spoke openly and honestly about their struggles, but they also wanted to turn their challenges into what made them feel empowered. Taking inspiration from America Ferrera’s TED Talk, “My Identity is a Superpower,” our students shared their stories of being fighters, embracing their Latina identities and finding a sense of belonging amidst discrimination and worry of undocumented relatives being deported.

I can’t help but believe that the courage of these students to speak their truths is steeped in the humanity of the American Dream we set out to define in Spanish class. What we cultivate in the classroom eventually ends up impacting the entire culture of our school. When we humanize the perceived outsiders of society, we create a belonging based on empathy and a shared understanding of wanting to live a life where a student and their family can thrive in safety and joy.

While the American Dream will always be linked to political contention and geographical borders, we must also remember that — like the demographics of our schools — our opinions and perceptions of it will also change. The dream can be achieved by believing in the power of education, just like my students and their parents, and just like my own grandparents. It can also be realized whether you cross a border to find your future, or even attend an all-girls Catholic school in the Midwest.

I hope students comprehend that the root promises upheld by the American Dream — prosperity, education and growth — reveal our human connections to one another. Mostly, I hope students at our school burst through their bubbles by challenging dominant narratives and stereotypical interpretations of migration and what it means to achieve the American Dream.

As educators and students, we must strive to center our humanity and uplift one another as we bravely navigate the possibilities of the dreams we carry inside — the dreams of our ancestors.