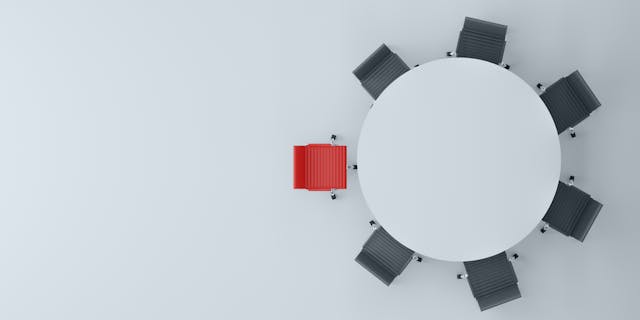

Last September, I was sitting at a long table in the sunlit conference room of my school, looking around at the many new faces on my school’s leadership team. At that moment, I had the jarring realization that my 17 years of service in the school were more than the rest of the team combined. We welcomed a new principal, dean of students, school psychologist and literacy specialist this past year. Other members of the team - the instructional coach, the band teacher and a sixth grade teacher - were only in their second year at our school. The next longest-tenured person, our student services specialist, was starting her fifth year.

While some of these staff are newer to teaching, most are experienced educators who have come from other schools, bringing their own backgrounds, beliefs and ideas to the table. Suddenly, I was the person who possessed the most historical and institutional knowledge of my school, and I felt responsible for speaking for the memory and experience of the other staff who have been here as long as I have.

The last decade has brought a lot of administrative turnover to my school and district. We’ve seen a cycle of new initiatives and ideas created by new leadership that disrupted our school structure and culture. The membership and purpose of our leadership team have changed along with our staff meetings, communication patterns, school-wide expectations and processes for student support and intervention. Each of these changes impacts the climate of our school, and ultimately, the student experience. Some of that evolution is natural, but too much at once can negatively impact school culture and cohesion. As more new staff arrive with new ideas, what does my institutional knowledge matter as my school goes through change? Does that memory have value and use, or does it hinder progress?

Being a veteran teacher, telling stories about the past was never something I envisioned for myself, but it is a role I’ve wound up playing. Over the course of this year, I’ve struggled to balance representing the history and culture of my school with my desire to support our ongoing and ever-more-pressing need to adapt. Aging gracefully is difficult for all of us, but as a teacher, it’s been trickier than I expected.

You Can’t Be What You Were

I started at my school as a second-year teacher in 2006. I had just moved from New York City to suburban Wisconsin, fresh out of my degree program and full of ideas for innovation. While the school I was coming to had a great reputation and strong outcomes for most students, I was replacing a teacher who had been there for over 30 years. I was confident in my approach and saw myself as a firebrand, ready to come in with my punk rock energy to change things and move on, keeping with the “move fast and break things” ethos of the dot-com era.

Yet, I am still here, and things haven’t changed as drastically as I hoped. When I hear others talk about change now, my reaction to it isn’t the same as it used to be.

Now, I feel compelled to talk about what we’ve tried before, what’s worked and what hasn’t, while also defending my colleagues against accusations of being unwilling to change – of being stuck in our ways. After a mid-year professional development session, I was debriefing with the leadership team when my veteran colleagues asked questions about the why and how of what we were doing, the school’s commitment to the changes, the costs and trade-offs, and where else the ideas had worked. The team interpreted much of that questioning as hostility and fear. “Teachers here are afraid of change,” suggested a new colleague, and I felt a surge of frustration as my mind flashed through the history of past reforms and initiatives that have been unsuccessful over the years.

While new colleagues hear hostility and fear, I hear my veteran colleagues asking healthy questions, because I know they want and expect to have a voice in our direction. Our concerns come from a place of having tried things before that didn’t work, and wanting so much to find something that will. We carry the scars of those past experiences and I’ve spent more time than I ever wanted trying to explain how we got to where we are. However, I’d be lying if I didn’t also acknowledge that I worry that maybe we are comfortable and want to keep it that way. Change is hard, and we find lots of ways to resist it, even when it can lead us to what we want. For as long as I've been teaching, we’ve struggled to make a meaningful dent in our most persistent problems.

As a veteran teacher, I am part of the system. I’ve been complicit in producing inequitable outcomes for my entire career, even though I’ve been working to change it. Looking at our school’s State Report Card, the disparities in our ELA outcomes between Black and white students have gotten worse over the last 12 years. Obviously, the responsibility for these outcomes doesn’t fall solely on me. Nonetheless, I can’t hide the fact that I’ve been a part of it.

I threw a lot of energy over the years into different reforms and ideas that would make the school more inclusive, more engaging, more relevant, more successful and more equitable. We’ve explored project-based learning, character education and extending the school day. Looking at the same results, what do we have to show for it?

We’ve Tried That

I desperately want schools to change but the kinds of change I hear being discussed sound so familiar, I don’t see them leading anywhere different. Sitting through a recent reform pitch from an organization we’ve partnered with to make our outcomes more equitable, I could see many of our old practices reflected in what they were proposing. I watched my newer colleagues look on with excitement about an innovative future, and all I could remember was our attempts to get to a similar place in the past. But saying so out loud felt pointless, like I would just be another old teacher saying it couldn’t be done.

Sometimes, part of me wishes I could sit around that table, forget what I’ve gone through and grab onto this new work fresh with the enthusiasm I used to feel for the next big thing. That was important energy that helped fuel change in my building before, and schools will need it if we’re going to evolve. Remembering that part of my teaching identity is important, but I need to pair it with what I’ve learned.

My institutional knowledge helps me see where we’ve gone wrong so that we can improve our chances of success next time. It’s useful as long as we’re committed to learning from it. Our past experiences won’t show us exactly where we need to go, but they can help us find effective ways to get there. In a period of substantial turnover, learning from those who have been there, especially those who have stayed, can teach us what is possible.

I wish that over the last decade, new leaders and colleagues would have spent more time learning about what our school had tried and what we thought was working. Bridging the gap between those new to the school and those who have been here is vital for creating a strong culture and foundation necessary to grow. Creating a habit of dialog and listening where new and veteran staff talk about their experiences, goals, and motivations – so that veteran teachers who say “we’ve tried that” aren’t heard as saying “it can’t be done” – can help us avoid the traps and pitfalls that have occurred in the past and help guide us to success in the future.

Tinkering Around the Edges

Lately, I’ve come to the conclusion that when turnover and constant change are a feature of the system, not a bug or glitch, it can lead to a false sense of progress. New initiatives make us think we’re making a difference – to feel like we’re doing something – when we are only tinkering around the edges. My experience shows me that we need to talk more about ideas that are bigger than tweaking an old system, which may even seem impossible if we confine our thinking to what schools are like right now. I want to help folks new to my school see that our effort and energy to change needs to go deeper. We need new energy to propel us forward, aimed at the knowledge of what we’ve done before.

As I return to the conference table this coming fall, I’m asking myself whether I have the energy to keep trying new ideas, or whether I’ve seen it all and been defeated by the insurmountable challenge. I know the shared experiences of the past year have formed a common understanding that will help us grow. I still believe that the work can be done, and we can create schools that produce equitable outcomes and prepare students to live in a diverse democracy with the skills they’ll need to navigate an uncertain future. To accomplish this goal, I need to continue to tell the story of what we’ve tried and encourage those around me to dream bigger. Schools are going through many changes, and how they adapt to that change – by learning lessons from the past and incorporating new ideas and energy – is essential to creating viable schools of the future.