Two years ago, EducationSuperHighway was getting ready to hang up its proverbial hat. The nonprofit said it had reached its goal of ensuring that 99 percent of U.S. schools were connected to high-speed internet, a boon to digital learning. Founder and CEO Evan Marwell was even looking forward to a sabbatical after eight years leading the organization.

But then—as we all know too well—the pandemic hit.

“My phone started ringing, and people in D.C. were calling, governors' offices were calling. They were saying the same thing,” Marwell recalls. “We don’t know how many of [our students] have internet or how to connect them.”

EducationSuperHighway created a tool to help schools identify students without internet access at home and, in the process, learned a lot more about the digital divide. Instead of closing up shop, the organization is launching a new campaign that focuses not on schools but on the 18.1 million U.S. households where cost is the primary barrier to connecting. Its plan for reaching that goal is outlined in a new report “No Home Left Offline: Bridging the Broadband Affordability Gap.”

“Despite the historical narrative about building infrastructure in rural America, two-thirds of the digital divide was that people couldn't afford broadband connections that were offered at their home,” Marwell says. “We saw this was a problem that can actually be solved, but it’s going to need an effort just like the effort to connect all the schools.”

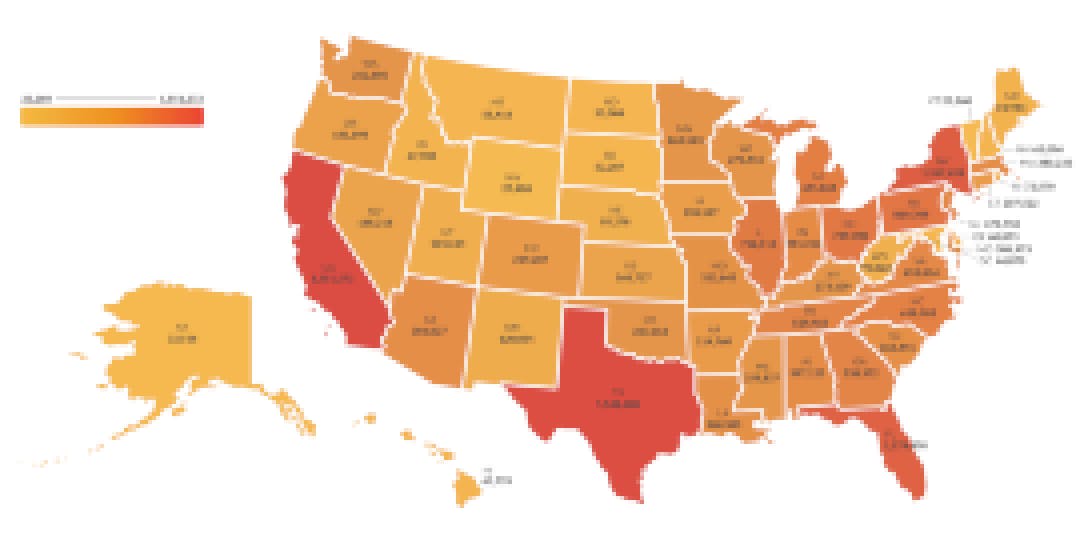

Source: EducationSuperHighway

Who’s Impacted?

Solving the broadband affordability problem is going to take everyone, Marwell says, from Capitol Hill lawmakers who control the federal purse strings to school districts that are best positioned to identify students in need of internet access. But the time to act is now, when the pandemic has revealed how deeply the digital divide impacts those who aren’t connected at home, he argues.

“Our country realized we are all worse off when 80 million Americans don’t have access to the internet,” Marwell says. “We are never going to have more political will or energy across the spectrum to solve this problem. If we don't solve it now, I don’t know when we will.”

In its report, EducationSuperHighway identified unconnected communities as those where at least one in four households lack home broadband.

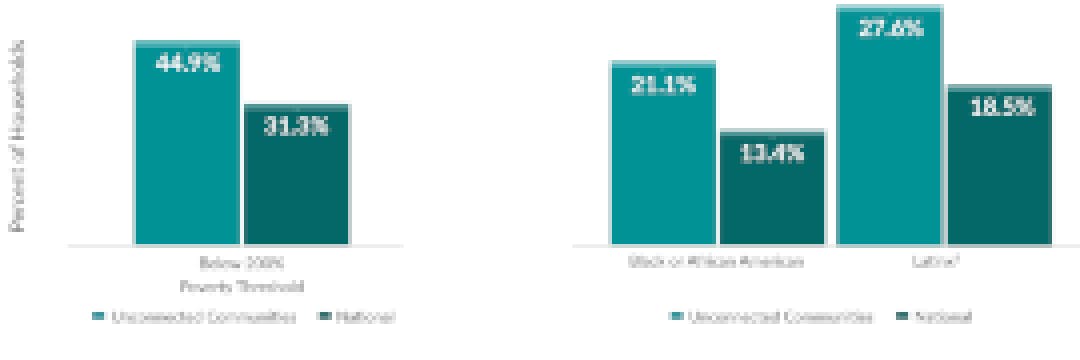

Black and Latino communities are disproportionately impacted. African Americans make up 13.4 percent of the national population but 21.1 percent of households in unconnected communities. The gap is even wider for Latinos, who make up 18.5 percent of the national population but 27.6 percent of unconnected communities.

Education factors in, too. Those with less than a high school diploma represent 27.4 percent of unconnected households, according to the report, compared to just 13.3 percent for those with a high school diploma and 4.5 percent of households with a bachelor’s degree or higher.

“Households in America’s most unconnected communities and those with less than a high school education are precisely the households who most need a broadband connection to find better jobs, educate their children, connect with affordable healthcare and access the social safety net,” the report says.

Going Beyond Awareness

Building awareness of low- and no-cost broadband programs is part of the solution, EducationSuperHighway officials say in the report. More than 6 million people have used the Emergency Broadband Benefit, which provides a monthly $50 discount for any internet service provider. That sounds like a lot of participants, Marwell says, until you compare it to the 37 million people who are eligible.

But it’s going to take more than awareness to get people onboard. They have to believe the programs will help them, and they need guidance on how to enroll.

“One of the things we really learned: trust is a big issue,” Marwell says. “People think, ‘This is too good to be true. You’re going to give me free internet? There’s got to be a catch.’”

Families also need help navigating sign-up processes that can be confusing or overwhelming. EducationSuperHighway’s report highlights the success of the Clark County School District, which serves the Las Vegas area. The district identified students without internet access, reached out to those homes directly and set up a concierge center to help people sign up with the local internet service provider. Marwell says the strategy got more than 80 percent of students connected to the internet at home.

“I heard about a district the other day that had 3,000 codes to give out for free internet service, and 76 families took them,” Marwell says. “You can’t just do general marketing.”

Scaling Up

Ever notice how you don’t have to convince people to use Wi-Fi at coffee shops or hotels?

EducationSuperHighway noticed that, too, and part of its strategy to close the affordability gap is getting free Wi-Fi in multi-family housing. It estimates that up to 25 percent of the digital divide could be closed just by offering free Wi-Fi at low-income apartment buildings, according to its report. Funding for just those types of programs would be covered by the $42.5 billion in broadband infrastructure that’s part of the yet-to-be-passed federal infrastructure bill.

Marwell says the nonprofit is already piloting the apartment Wi-Fi program in Oakland, Calif., where EducationSuperHighway has set a goal of connecting 5,400 households in 127 apartment buildings to the internet. It’s also running pilot programs with three school districts getting ready to launch broadband adoption campaigns with several cities and housing authorities.

“We’re using those pilots to perfect the program [and] understand what the right steps are.” Marwell says. “That’s the work of the next 18 months, setting the stage to connect people at scale.”

In many ways, the nonprofit is tackling an even bigger problem than the one it set out to solve when it was founded, Marwell says. Its original goal called for high-speed internet access at roughly 100,000 schools. Now it’s sights are set on more than 18 million households—nearly 47 million people.

That also soundly puts the kibosh on any plans Marwell had for a sabbatical. Maybe in another eight years.