Yessika Magdaleno, owner of a home-based child care program in Orange County, Calif., is a problem-solver by nature. When she opened her program 20 years ago, she attracted families by expanding her hours to nights and weekends to accommodate those with non-traditional work hours. When she felt that her own children were not well-served by the local afterschool program, Magdaleno expanded her program to include afterschool care.

But even with her knack for problem-solving, Magdaleno was unprepared for the extreme stress and uncertainty of being an early childhood educator during this pandemic year.

There were small challenges, like getting 2-year-old children to wear masks, or finding electrical outlets to accommodate all the laptops that the school-aged children in her care needed for remote learning. There were major headaches, like figuring out how to stretch state subsidies intended just for afterschool care to cover the costs of full-time care. There were humiliations, like the time, early in the pandemic, when Costco wouldn’t accept a letter authorizing Magdaleno to purchase goods for use in her “essential” business.

But most of all, there was fear. Fear about maintaining her business when the country shut down. Fear about paying her staff when enrollment declined. And at the root of it all, there was fear about the virus.

There was fear every time a child arrived with a runny nose, and every time a child mentioned attending a birthday party over the weekend. There was fear with every call that Magdaleno—a leader among home-based providers in California—received from worried colleagues.

At first, they called asking how they could keep their businesses afloat, how they could get the cleaning supplies they needed. Later, providers called to share the news that a student’s mother had tested positive, that a husband, an uncle, a mother, a sister was sick, that a friend was in the hospital.

In December, she said, “Today, I got three phone calls from three providers that got infected, and they have to close. And they don't know if they're going to get paid. That's how difficult we're living.” There’s not a lot she can do. “And listening to them, you can’t say, ‘Well, everything is going to be O.K.,’ because you don't know if everything is going to be O.K. [It’s] heartbreaking, because you have to be strong for them."

Magdaleno understood the fear viscerally. The virus came for her family, too. An uncle died. Her brother and his family were sick at Christmas. Things got so bad that Magdaleno asked if her brother had a will. What would happen to his kids? She wanted him to be prepared. It was a conversation that people were having all over Magdaleno’s community in Southern California, where COVID-19 rates were exploding.

But amid all the fear, there were good moments, too. The children in her program seemed happy. The families participated in a gift exchange at Christmas. By late winter, the school-aged kids went back to their K-12 classrooms and Magdaleno could concentrate on the babies and preschoolers for most of the day.

And, by March, after the surge, there was hope, too. Magdaleno saw that educators in her program let go of some of their fear once they got vaccinated. Daily COVID-19 case counts fell. Asked to describe her emotions in March, Magdaleno said that she was “blessed, confident, stable.” The fear was loosening its grip, day-by-day, even if there were still scars of this pandemic year.

Early childhood educators have faced a year like no other during the pandemic. It’s been a year punctuated by fear, panic, frustration, anxiety and, at times, hope. From December 2020 through May 2021, EdSurge followed seven early childhood educators from across the country. The group is comprised of women who work in a variety of roles and settings, from California to Pennsylvania. Participants were provided a small stipend for participating in this research project and took part in monthly interviews and surveys. Through these research activities, we learned, in deeply personal terms, what it looks like to teach young learners, engage with families, run businesses and manage personal and professional stress during the pandemic.

This is the story of how those educators managed—from mid-March 2020, when many early childhood education programs closed their doors, unsure if or when they would reopen, through the darkest moments of a deadly winter, to plummeting COVID-19 case counts and rising vaccine levels that the country experienced in spring 2021. This oral history presents those experiences in the words of the practitioners themselves. They’ve been condensed, lightly edited, and assembled by EdSurge researcher and labor historian Rachel Burstein.

Meet the Educators

Adrienne Briggs is owner and educator of Lil’ Bits Family Child Care Home in Philadelphia, a program serving children from ages 0 to 5.

Briggs is licensed to enroll six children, but had only three children in her program in December 2020. Briggs explained, “I have not been comfortable bringing in anybody brand new [amid concerns about safety during the pandemic]. And also, I'm not getting the type of calls that I used to because so many people are working from home.” Because she doesn’t have a mortgage or employees, Briggs was able to shoulder the lost revenue.

Shelley Jolley is an education manager and disability specialist at Rural Utah Child Development Head Start, which serves children from ages 0 to 5 near Price, Utah.

Jolley and a colleague supervise all the educators among 13 Head Start classrooms across 17,000 square miles. In addition, Jolley monitors compliance with requirements around students with disabilities.

In normal times, Jolley spends a lot of time traveling, visiting classrooms and teachers and conducting assessments and observations. She was used to video meetings even before the pandemic, given how spread out programs in her service area are, but shared, “It’s harder to build the rapport and the relationships over Zoom.”

Yessika Magdaleno is owner and educator of Little Flowers, a home-based child care program serving children from ages 0 to 12 in Garden Grove, Calif.

Magdaleno’s program is open to young children full-time, including nights and weekends. In addition, children who attend the elementary school across the street join for afterschool care. During the pandemic, Magdaleno supervised elementary-aged children during their remote learning as well.

Magdaleno explains the realities of being a family child care provider, a role she’s held for about 20 years. “You are the nutritionist, the teacher, the one that cleans, the ones that take care of the business account. And if you have employees, you take care of the employees, their payrolls. So you're the one doing everything.” These challenges have been even more acute during the pandemic, as Magdaleno sorts through unclear and changing rules and regulations, and as she struggles to protect the health and safety of the children in the program, her employees, and own family.

Maríaelena Lozano is owner and director of Westchester Academy and Learning Center, a bilingual program serving children from ages 0 to 8 in Miami.

Lozano’s program is licensed to serve 56 students through third grade, but she doesn’t currently have the space to accommodate students beyond first grade.

Eight years ago, Lozano opened her school with her brother, a retired police officer. Lozano didn’t close her program at all during the pandemic, but through May of last year she had just three students. By December, Lozano’s enrollment had rebounded, and she described her biggest challenge as one of space: “I don't have the space to grow because I'm in a rented location. So one of the goals for me for next year is to purchase a building.”

Paula Polito is owner and director of Beary Cherry Tree, a child care center that serves children from ages 0 to 5 in the Greater New Orleans Area of Louisiana.

Beary Cherry Tree has been in Polito’s family for three generations, though Polito has expanded it significantly to its current capacity of 225 children, with 14,000 square feet of space, and 60 teachers on staff.

Managing Beary Cherry Tree hasn’t always been easy for Polito. She recalls when Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans in 2005. “We lost our house … I came back to my child care center. I had $600,000 in damage. My entire building, one of the walls was on the ground and we were pregnant with our first child. I always said, ‘If I have to do another Katrina, I won't be able to do it.’” Polito describes the pandemic as, “Katrina times 10.”

Kathy Yanez is owner and educator of Nuestra Casita Nursery, a home-based program serving children ages 0 to 5 in Santa Monica, Calif.

Yanez opened her program in August 2019, after two decades as a preschool teacher in a center-based program. Yanez says, “I’ve always dreamed about being a business owner.” She “put everything I had” into renting a home to use for her program, leaving the affordable housing unit where she and her teenage daughter had been living. “I just relied on my experience, my knowledge of early childhood, and a lot of praying,” Yanez remembers.

Just as Yanez felt that she was on firm footing with enrollment, staffing and curriculum, the pandemic struck. When we spoke in December, Yanez described the first six months of the pandemic as “going into survival mode. ‘What’s going to happen next? Can I pay my rent for next month? What happens when the loan is depleted?’ It's just a lot of that.”

Shemeakia Zinnerman is a substitute teacher for 3- and 4-year-olds at Guilford Child Development, a Head Start provider in the Piedmont region of North Carolina.

Zinnerman has been working in early childhood education since 1999. She is pursuing an associate’s degree that will allow her to become a lead teacher.

The work is challenging, and can be heartbreaking, but Zinnerman says that it is deeply needed. When we met in February, she said that at Head Start, “We take on the children that nobody thinks about,” such as children with special needs and those who do not have loving, nurturing environments at home. “It's hard. Sometimes I want to cry, to be honest,” she says.

Spring 2020: ‘The Most Depressing, Scariest, Uncertain Time of My Life’

By the time we began speaking with early childhood educators in December, there was some rhythm, if not exactly stability, in the day-to-day experiences of educators. But to a one, practitioners recalled the early days of the pandemic as traumatic, especially for owners who had to make hard decisions about whether to close, how to make payroll and mortgage or rent payments, whether to charge families, and how to keep children and staff safe.

Adrienne Briggs: I shut down March 13 and did not open back up till June 9. That was the most depressing, scariest, uncertain time of my life because we were constantly being fed different things through the news. Everything was constantly changing. Didn't know whether we were right, left, up, down—none of that.

And with being in this business so long, I had stability, but that foundation felt like it was snatched totally from underneath me. So there was no stability. I didn't know how—didn't know from month to month—whether we were going to be paid, whether we were opening, just didn't know. And I run the ship by myself. So this is my sole source of income. I don't ever want to see a time like that again.

Maríaelena Lozano: We never shut down. Many parents just became afraid, and half the students didn't show up on Wednesday, March 18. I understood what was going on, and I called parents.

Everyone was like, ‘Do I still need to pay you, Miss Mel?’ I knew what was coming, so I said, ‘No, you guys don't have to pay me right now. If you're not going to bring your children, I understand.’ What am I going to do? Tell them they have to pay me? Most of them weren't even working themselves.

By mid-April, we're already a month into the pandemic, and I end up with probably seven children in school. I had been trying not to cut anyone’s hours. But depleting funds was all I was doing. I was lucky enough to have something in the bank that kept us rolling.

Then the last week of April came. I had three children in school. I was like, ‘I'll do it myself,’ and that's really what I did. I sent everyone home for about 10 days. I was working mad hours because I was taking care of the students and then I was preparing everything for the PPP, and just doing everything I needed to do. I was working seven days a week. I was very stressed out, but the three parents that needed us, they needed us. They were still working. Single moms. What are they going to do?

Paula Polito: We shut our doors on Friday, March 13. I didn't have a crystal ball, but what I did know is that I was about to lay off 50 full-time women who needed the check I gave them to put food on their table.

So I told everybody they were about to get a check so they'd have a little bit to float on, but I said, ‘I want everybody to get on unemployment right now.’ We didn't reopen our doors until June 1.

Kathy Yanez: When COVID hit, basically my numbers started quickly decreasing. I had about 11 families, and three got out. Because of the cost of rent and the cost of managing a business, I saw if I were to lose any more families, that would be it for us. That month—I think it was April—I sent my landlord a notification that I was losing numbers quite quickly and that I would probably have to close. And my daughter and I would just end up homeless.

But the families that stayed continued providing tuition monthly, so that covered our rent. And slowly, slowly, as all the policies came into place with COVID, families started coming back.

I'm very shocked that I'm still here. And I'm grateful to God that I'm still here. I prayed a lot.

Summer and Fall 2020: ‘It Was Just a Lot … Trying to Stay Afloat’

In the summer and fall of 2020, practitioners began to adopt new routines. Programs that had closed reopened for in-person learning in most, but not all, cases. Enrollment rebounded for many programs. Practitioners contended with quarantines and school closures in some cases. Goods became more readily available, but the costs of conducting business increased as providers invested in cleaning supplies, outdoor structures and staffing to accommodate stable groups of students. And providers were still navigating new guidelines and funding options.

Kathy Yanez: For the first two-and-a-half months, I was really trying to find the loans available. I didn't understand, because everything just flooded in about PPP loans and who qualified, who didn't qualify.

Those were really new waters for me. It was just a lot—the stress of what was going on, trying to stay afloat, and then not qualifying for PPP at the beginning. Eventually, I did end up with an SBA loan and a PPP loan.

Paula Polito: It was a Thursday in October and one of my [part-time teachers] tests positive. We communicate, we prepare to shut that classroom down. The next day, an adjacent classroom, another teacher tests positive. So we're communicating with all the families that we’re having to shut down that classroom.

Fast forward to Sunday, my director who's pregnant winds up testing positive. Sunday night, another teacher and Monday morning another teacher tests positive. So that's when I said, ‘We're calling it.’ It's what’s safest to do. But it's still frustrating because you don't want to do it.

And that was one of the risks, right? I mean, I knew when I reopened my center, I could potentially get COVID. And I was willing to take that risk because, if not, I'm going out of business.

Shemeakia Zinnerman: You work harder now—I mean, from home—than you would in a classroom. A classroom, you can be hands-on. I can really help the child with his own [work], but you can't really do that when you're doing virtual … We see them doing colors, shapes, numbers on the screen. If they're drawing, we’re watching, like, ‘How do they hold a pencil?’ We pay attention. That's how we have to get some of our assessments.

December 2020: ‘We’re Just Adding on to the Stress.’

At the time of our December interviews, most of the United States was setting records for COVID-19 case counts, hospitalizations and deaths on a near-daily basis. Meanwhile, early childhood educators who were part of our project had adjusted to new routines and guidelines, even as they remained anxious about their own safety and the safety of children and families that they served.

Maríaelena Lozano: It is scary to be working with the students, because we don't want to get sick, but we also don't want to spread the disease or the virus out. If we're not the only normal moment that the child has, if those eight hours that they're in school are not normal for them, then we're just adding on to the stress. We're worried about our money, and we're worried about not having a job, and we're worried about all these things. Nobody's worried about the students.

Shemeakia Zinnerman: I do worry about my safety, [as we prepare to open in-person]. Because you never know what the kids have been around. Yes, ma'am. I do. It's going to be hard. But our center is getting stuff to put in place to help protect us.

I feel like some of the challenges are you don't know the [students] that need help, have behaviors, IEPs. You don't know exactly how they're going to do, really, when they do get in the classroom, you know? That's a challenge you're going to have. They're at home with their moms right now, but how's it going to be when we go back to a real classroom? To me, that's going to be a challenge.

Adrienne Briggs: A 5-year-old in my program was like, ‘I don't like COVID, I'm tired of COVID. I want to be with my friends. I want to be able to hug my friends. I want to be close to my friends.’ Because that was a big change. We hugged each other coming in, going out.

They don't have a problem with the masks. Even if somebody's mask is slipping down, they'll remind each other, ‘Fix your mask.’ They help each other count to do the hand washing. I bought special booties for them to put on to cover their shoes.

January 2021: ‘I Am Working Around the Clock.’

Nationwide, daily recorded COVID-19 cases peaked in January, with average daily cases well over a quarter of a million for stretches of the month. Educators in our project were not immune to this trend. “Extremely prevalent.” “Has spiked.” “Extremely high.” “Still increasing.” “Numbers have risen.” “Big concern.” These are some of the words that educators used to describe the COVID-19 situation in their communities.

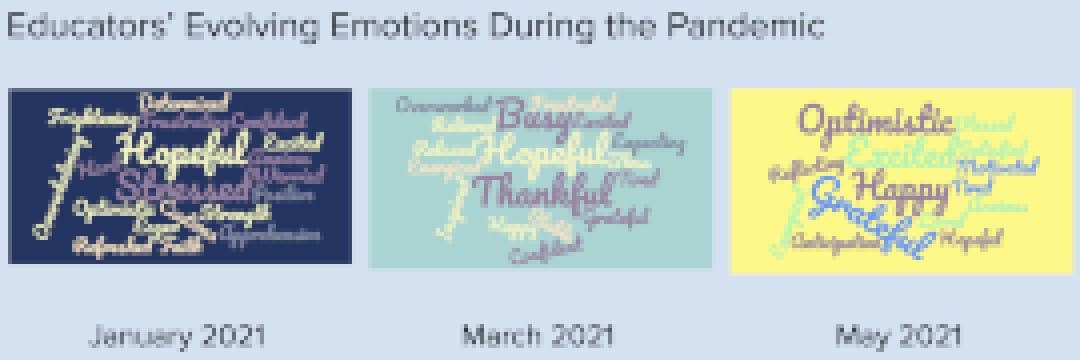

Even in the midst of the pandemic, some educators tried to stay positive—vaccines were on the horizon, and many people began to envision the end of this crisis. When asked to share three emotions that they were experiencing at the time of the January survey, a majority of participants listed “hopeful.” At the same time, most participants expressed that they were anxious, apprehensive, worried or stressed.

Kathy Yanez: I am working around the clock. COVID has given us a scare. We had two positive COVID cases. We had to keep the program closed for three weeks and tested three times before reopening child care. This has been a very costly experience for all families and staff.

I got the rapid test. Within 20 minutes, they said, ‘You're positive.’ Then I said, ‘Oh, wow. So I have to remain closed for two weeks.’ I let my parents know. It was quite frustrating for them because everybody was ready to come back. It was shocking. I was shocked, and then I was really scared because I was, like, ‘Oh, my goodness, I don't want to end up in a hospital.’ Luckily, I never had any symptoms.

Shelley Jolley: We are supporting each other when staff have to be out for COVID and providing virtual services for families who are quarantined or prefer virtual services. Our staff and families have been so great about following our COVID plan, which includes wearing masks, cleaning and sanitizing, and social distancing. We have only had to close three classrooms for a short period of time throughout the last year.

We are excited that the vaccine has become available.

Yessika Magdaleno: I received texts and phone calls from fellow providers that have closed due to COVID-19, been exposed to the virus, been infected, have family members that have died because of the virus. And we still have not been recognized to be important at the state level in California.

February 2021: ‘There Has to Be a Point That It Has to End. And I Think We're Reaching That Point.’

By February, COVID-19 case counts were retreating nationally, though still high in many areas. Most of the educators in our group were excited to receive the vaccine, though access remained limited even in places where early childhood educators were prioritized.

Paula Polito: There's hopefulness. I just went to the cafeteria to warm my lunch up, and one of my teachers said, ‘Paula, I got my vaccine. It's scheduled for Saturday.’ So that’s what I'm hearing. I think across the state and within our little community here, people are feeling confident because they are getting vaccinated.

One of my teachers came in today, and she said, ‘Paula, I just want to let you know how much I really enjoyed [the professional development class that the center offered]. I forgot how much I really needed that.’ That was just so good to hear. Our teachers still want to get back to that rich work we were doing and stop worrying about, ‘Do we have to quarantine a class?’ ‘Am I going to get COVID?’ ‘Is my kid going to get COVID?’ They didn't sign up for that. They signed up to teach young children.

Kathy Yanez: It is upsetting to not be included in the first round [of vaccine distribution], especially because we have been open the whole time. We feel very exposed, especially working with children. I don't want to get angry. At times, I do. I'm like, ‘Ugh, I'm so mad,’ but I let that go really quickly. My energy does affect the way children feel around me, and so it's very important for me to [be] composed, to maintain a healthy persona.

I think you have to just think like that because otherwise, you will let yourself fall into a very deep depression. I think, in this time, it is very easy to do that—to become stuck in a depression.

Shelley Jolley: We have actually had COVID hitting Utah a lot harder. We've had to close two centers down for a few weeks, and we've had to quarantine several teachers just in the last month, so it's been a little crazy. We have a shutdown plan for COVID, with guidelines for teachers, so it's pretty quick to put in place the virtual visits and stuff. But it's just been challenging. The change is stressful for the kids.

Maríaelena Lozano: I feel like coronavirus has brought a lot of attention to early education, but it hasn't brought a lot of solutions. Those teachers, they still have to hug the babies. They still have to pick up the babies. They still have to change the babies’ diapers. At the end of the day, these are the risks we are taking. We're at a higher risk.

Adrienne Briggs: I know this is going to sound crazy, but it's not as hard now, I guess, because I've gotten into the pattern of doing extra cleaning and preparation to follow COVID-19 protocols. The day runs much smoother when the program is open five days a week. I'm able to capture more teaching moments rather than the redirection moments. And I see that joy back in the students because they're more so back into their normal routine and they're able to see their friends on a more regular basis.

Shemeakia Zinnerman: My biggest challenge is being a bus monitor. … On the bus, it's like a sheet of plastic that separates each child where they have their own space. It's one child to a seat, and we make it so they don't pass each other getting on and off the bus. It was a challenge at first, but I'm getting the hang of it. I like this better than being at home.

I protect myself. I always have on my mask, my shield, I'm always washing my hands, I always have on gloves. I make sure that the children's masks are on. I think I protect myself very well.

Maríaelena Lozano: People are forgetting that all of the stresses that we're experiencing, [the children are] experiencing them more, because they're seeing us stressed out. They don't have the logical ability yet to reason out what's going on. Students are talking about coronavirus like it's a person. I have a little girl at school that tells me, ‘When corona leaves…’ She's just so casual. ‘Yeah, when corona leaves, I'm going to go to Disney World.’ So, I laugh. I'm like, ‘When corona leaves, huh? O.K. We're going to work on corona leaving together.’

Yessika Magdaleno: Emotionally, we're not right. We're not right. We're stressing out.

There has to be a point that it has to end. And I think we're reaching that point, because numbers are going down. People [are] being more aware of what they need to do.

Adrienne Briggs: I'm content with my four students because I do know their whereabouts, their comings and their goings for the most part, so that's not a stressor. I do have that level of trust with them, that if something was wrong with one of the children they would really say so. Prime example: One of the children had a runny nose and was sneezing the other week. I let the mother know. The mother kept her child home until the runny nose stopped. It was never any fever or any real COVID [symptoms], but just for the precaution of her own child and the rest of the children here and myself, she kept the child home. So that's the type of families that I have.

March 2021: ‘I Am Beginning to See Some Normalcy.’

By March, nationwide COVID-19 rates were at their lowest levels since the fall. And most early childhood educators across the country were eligible for vaccines. COVID-19 protocols remained largely unchanged for educators in our project.

With declining cases and growing availability of vaccines, educators in our project were more positive in their outlook than in the past. Asked to name three emotions they were experiencing at the time of our March survey, nearly half expressed that they were “hopeful,” “thankful,” and “busy.” In contrast to previous months, 13 of 17 listed emotions were positive, while only three— “tired,” “overworked,” and “frustrated”—were negative, and one was neutral.

Paula Polito: Allowing access to vaccines for my teachers has given them the confidence to come to work feeling safe.

Shelley Jolley: We have some classrooms with children with behavior concerns. It is challenging to observe and address those virtually. We are still discouraged from traveling across counties and meeting with our staff in-person due to COVID concerns.

Adrienne Briggs: The past two weeks have been me acting silly with the children by dressing up in colorful wigs and Dr. Seuss headbands that represented different characters from his books. … I am beginning to see the light at the end of the tunnel and some normalcy.

Yessika Magdaleno: I lost some kids that I haven't been able to replace. Of course, we lost some income.

Many providers have already received their vaccines, and that has given them peace.

Maríaelena Lozano: I have taken some time away from my schooling to focus on the growth of the business and to search for another building. I am also focused on securing good teachers and aides for my classrooms because our growth has been such that we require more help now to continue providing quality early education services.

As a whole, I feel like many things in my life are aligning. It is not a specific interaction or occurrence; it's more like everything. All my hard work, all my energy output, all my prayers—just everything is working itself out. Sometimes, when I realize it, it feels surreal.

Shemeakia Zinnerman: I am looking forward to getting back to normal, to the day I do not have to wear a mask to breathe the air.

April 2021: ‘A Lot of the Stress Has Been Released.’

By April, COVID-19 case counts were continuing to decline as more of the adult population got vaccinated. Some educators reported taking a break from COVID-related news consumption to allay their nerves. Most educators in our project had received their vaccines or had scheduled appointments. A few owners felt stable enough in their enrollment and revenue that they were considering expanding their operations. Many were experiencing the effect of consumer good price increases. All were looking to the future with hope.

Adrienne Briggs: A lot of the stress has been released. Most of the stress was just the unknown, just not knowing from one day to the next what the safety levels were going to be and everything.

Yessika Magdaleno: Things are much better. We're more stable. We know what we have to do. I think we have the rules already in our mind. The children are more stable as well. They know they have to wear their mask, they have to wash their hands, they have to take their temperature. So everything is more stable. My helpers, too, they're not anxious anymore of what can happen. Most of us already have the vaccination, so they feel more secure.

Kathy Yanez: I'm pretty happy. Pretty happy I have the vaccine. We continue to wear our masks, although we are vaccinated. And just out and about, it just feels comfortable being around a larger group. The vaccine brings a lot of hope. There’s hope that we can work and not feel so vulnerable, that I won't end up in the hospital on a breathing machine. There’s hope that this business, this place, is not going to disappear.

Maríaelena Lozano: Things are great. I don't know how else to say it. I always want to be thankful and mindful of the things that I say, because I don't want to appear like I don't understand how lucky I am. I know that I'm lucky. Things are good. Things are so good in the school. We're going to buy a building. That's going to happen. We're going to maybe have a second school. As long as I can work with my landlord, then I'll have two locations.

Shelley Jolley: I think we're in the recovery, moving forward mode. So it seems like it's looking up. We only have three weeks left of kids in session. And so the really exciting thing, too, is today, we just got the notice that we don't have limits on our class sizes now, so we can open up the classroom to all of our students.

Shemeakia Zinnerman: I said, ‘I know [co-workers who’ve received the vaccine are] fine, then I shouldn't have a problem.’ And I didn't want to limit my mobility. I want to be able to get out and go. And after a while, that's about the only way you're going to be able to get up and go—is if you had the vaccine.

My first vaccination, I was scared. I was panicky and I was scared. The lady played some music to calm me down. For the second shot, I wasn't scared. I was straight. I was in and out, and it was fine.

May 2021: ‘Thank You For Teaching Me To Be a Better Human.’

In May, vaccines were readily available, and national COVID-19 rates were at their lowest levels since last summer. Many educators in our project were more hopeful about the future than they had been at any point since the pandemic began.

“Excited.” “Happy.” “Grateful.” “Optimistic.” These were the emotions that more than one member of our project used to describe their mood during the month of May.

Maríaelena Lozano: A first grader wrote me a card for Teacher Appreciation Day that read, ‘Thank you for teaching me to be a better human.’ I'm still over here crying.

Shelley Jolley: Now that our COVID restrictions are lifting, I was able to visit three program sites and deliver a small appreciation gift to each staff member. It was so great to see them in-person and let them know how much we appreciate all they do for children and families!

Kathy Yanez: My program has grown into infant, toddlers and preschool programs. I am running all three programs with the help of new staff members. There are a lot of families in need of child care, plenty of applicants on our waiting list.

As summer begins, educators in EdSurge’s project are looking toward the future. For the first time in over a year, many are looking forward to visiting with family and friends without deep fear that they will contract the virus.

All are thinking and talking about “getting back to normal,” as Paula Polito describes it. But their sense of what normalcy might entail, and their timelines for when it might be possible, vary.

Polito looks forward to the new school year in New Orleans, when there are “no masks or temperature checks” and when she is able to “welcome parents back into the center.”

Maríaelena Lozano is also looking forward to “a smooth new school year,” but she can only guess at whether that will be possible, particularly as changes to Florida state guidance concern her.

But to a one, the educators agree with Shemeakia Zinnerman, who says, “I am looking forward to a brand new year with the children.” A new year, they hope, will bring a fresh start.