When it comes to troubleshooting for her children’s remote learning, it seems like Barbara Lopez has done it all.

Depending on the day, the Miami mom could be supervising just two of her young children as they log into their virtual classrooms―or she could be helping all four. She’s handled Zoom breakdowns, juggled multiple parent support group chats and gotten her kids fed during their four different lunch times. And she’s done it all while working from home part time as a university lecturer (her husband works remotely full time).

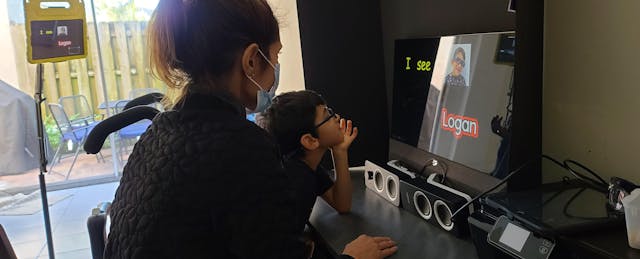

Varied as her days may be, one thing is constant: Her presence by the side of her youngest son, 8-year-old Logan, during class time. Logan has cortical visual impairment—a neurological condition—along with additional special needs, and Lopez stands in for the professionals who would be helping him in the classroom during a typical school year.

“I can’t just turn on the Zoom, put him in front of it and then go help the other kids,” Lopez explains. “There has to be somebody sitting next to him helping with the technology and getting him engaged in what’s going on. When the teacher shows him something that’s not accessible for him, I have to figure out, ‘Do I enlarge it to remove the visual clutter? Do I turn off the screen and let him just listen?’”

As parents and educators continue to navigate remote learning, children with visual impairments have the added burden of learning in virtual classrooms that aren’t designed for them. Hybrid and socially distant in-person classes present challenges of their own.

And looming overhead, there’s the worry about the time their children have lost in academic and life skill classes. Each parent knows there's a limit on the years their children have left in school, and the clock keeps ticking away no matter how much the pandemic has halted everything else.

Adjusting to a New Landscape

In the months immediately following the shutdown of schools across the country, researcher L. Penny Rosenblum and her team at the American Foundation for the Blind examined the impact of COVID-19 on students, families and educators. Their report, titled “Access and Engagement to Education Study,” surveyed over 1,400 parents and professionals in the U.S. and Canada.

The challenges faced by most students and families reeling from the shift to online learning was heightened for children with visual impairments, says Rosenblum, many of whom have additional special needs.

Fifty-six percent of the children of survey respondents had disabilities beyond a visual impairment. That required parents and professionals working together to adapt a curriculum that, in a school setting, is highly hands-on and individualized.

“If I have a child who has a visual impairment and a hearing impairment, I’m going to use sign language with that child where their hands are going to be on top of my hands. I can't do that through a computer, so how do I communicate with that child?” Rosenblum says. “I have to engage a family member, and they have to understand what I’m doing and why.”

Rosenblum says family members also grew in their understanding of core curriculum skills like how students with visual impairments learn to travel safely or use screen readers. On the flip side, technology caused stress in families where parents became navigators for students who could not use assistive technology independently. The tool might have been too confusing or taken too long to learn, she explains, or even required training by someone other than the student’s teacher.

Rosenblum says one issue that carried over into the fall is the systemic problem of access to information. Take for example a teacher who records a video demonstrating algebra equations on a whiteboard.

“If I have a blind student who can’t see that video, then that content is not accessible to me,” she says. “There’s a difference between accessibility and usability.”

Putting a Plan in Place

On paper, Sarah Chatfield says her family was positioned to be uniquely successful with virtual learning for her son when COVID-19 hit. The family lives in rural Wyoming, and 10-year-old son Jack, who has optic nerve hypoplasia, has used remote services throughout his life. Chatfield is also a teacher for students with visual impairments and is working toward a Ph.D. on how students learn braille via remote education.

“I feel like if you made a list of things that needed to happen so COVID didn’t disrupt learning … all those things were in place, and it was still incredibly difficult,” she says. “Hours and hours a day for him, and I don’t think the curriculum was accessible.”

Chatfield estimates she spent about three hours per day helping Jack when school moved online. Even with a great relationship with his school, visuals weren’t big enough, audio descriptions weren’t helpful enough and the learning platform was hard to use, she says. It was also physically painful after a certain point for Jack to be hunched over his school work to get close enough to see.

Chatfield knows that remote education for visually impaired students can be done well, she says, because she works with those children every day in her professional world. As a parent, she felt the same pressure as others to adapt the curriculum for him on the fly, not to mention the mobility and other goals that visually impaired students work toward.

“Everybody has to be onboard. There’s a reason why, when my kid goes to school, he sees five different professionals a day,” she says.

Schools in Wyoming are open now, and Chatfield says Jack is happy to be back around the kids in his class. But Chatfield was surprised to get resistance from the school when she asked them to develop an emergency learning plan in case COVID-19 forced them to go fully remote again.

The school insists there won’t be another lockdown, she says.

“Why wouldn’t you put something in place so if we go to lockdown again, the transition will be smooth? It’s very hard on the kid, the teachers, hard on everybody,” she says. “Having a plan in place would mean Jack still gets access to things his peers have access to. You’re saying, ‘Let’s just deal with it when we come to it.’”

Speeding Up the Tech Timeline

About 150 students are enrolled at the Austin campus of the state-run Texas School for the Blind and Visually Impaired, which reaches another 11,000 students through school district support and short-term programs.

Daniel Wheeler, instructional technology coordinator, says educators had about a week to let their new reality sink in when word came that the coronavirus pandemic would likely keep the school closed after spring break. What followed was a huge technology shipping effort for students who had returned to their homes across the state.

“We called it ‘crisis education’ in the spring,” he says. Many students access curriculum through tactile tools, braille readers and other physical objects, making Zoom calls a poor substitute for this type of learning. “A huge focus for me is training teachers to use educational technology in a way that’s effective with students that use assistive technology.”

When the school reopened in the fall, Wheeler was faced with a new set of challenges. He fixed the disruptive feedback caused by microphones in classes with both in-person and remote students. Interveners who sign for deafblind students were brought in over Zoom, and students in socially distanced classrooms had their voices amplified. The library now has a shipping area from which tactile materials are sent to remote learners.

“A lot of mainstream education tech is not designed with folks with disabilities in mind,” he says. “What might take very little time in a mainstream class requires a lot of upfront work and prep in our setting.”

When school was fully virtual, Wheeler says students with parents who worked remotely had better learning outcomes than those whose parents worked outside the home.

“I’m speaking anecdotally, but the students who came back to in person instruction first were the ones whose parents could not support them throughout the day like they needed,” he adds. “They were one of the reasons we wanted to provide in-person instruction opportunities as quickly as we safely could.”

Planning for the Future

All things considered, Michelle Contey says hybrid learning this fall went pretty well for her 18-year-old son Matteo, a student at Perkins School for the Blind in Massachusetts. The tech-savvy teen can access his remote classes and takes part in a Zoom music club just about every day.

Matteo has socially distanced classes on campus a couple of times per week. He is still meeting with mobility instructors. He still takes piano lessons. But there’s a gap in his education that gnaws at Contey: all of the life skill classes meant to prepare him for life outside the home. Try as she might to teach him on her own, she says it’s not a replacement for what he could be getting at school. And plans to let him live on campus part-time have been put on hold.

“It is stressful to me that I can’t get him what he needs right now,” Contey says. “I’m not going to live forever. I do want him to be independent. I would love for him to just live with me, but I'm not doing him any service that way.”

Rosenblum and her colleagues are wrapping up data collection for their fall survey, which will reveal what about 800-900 professionals and parents of visually impaired children experienced with the addition of hybrid and in-person learning. They plan to release their new findings in February or March. She says it’s an opportunity for people at every level—from parents to administrators to tech companies—to address both pandemic-related and systemic issues that impact their education.

“We can work to affect changes so our students with visual impairment really do have an equitable, inclusive education, Rosenblum says.

Those changes would impact people like Lopez and her son. There’s a part of their house that the family calls Logan’s office. It’s set up with his special equipment and adaptive seating, and there’s a stand for his iPad. That’s where he and Lopez start their daily routine by talking about the date, then move on to a little reading, math and some self-help skills. Lopez says she worries about Logan falling behind every day. It’s why she works so hard to get him every resource she can.

“Services end at age 21, no matter how much he’s learned, and there’s no pandemic clause where we’re going to get an extra year or two added to the end,” she says. “As special needs parents, you’re always running against a clock. You're trying to make up for the delay, and on top of that, add the pandemic. It’s insurmountable.”