Can a pacifier accurately monitor children’s neurodevelopment, based on their sucking patterns? Can vacant parking lots be redeveloped into libraries for children in “reading deserts?” And how can an AI-enhanced robot help toddlers improve language skills?

These were among the projects pitched at Early Futures, a conference hosted by the Omidyar Network, Promise Venture Studio, and Sesame Workshop in San Francisco on Nov. 27-28, 2018. The gathering convened about 250 early-childhood education entrepreneurs, funders and researchers united around a common vision: that the problems confronting the world’s littlest learners deserve the most attention—and money.

When it comes to fundraising, companies, including not-for-profits, shouldn’t be shy about asking for what they need, said Nancy Lublin, CEO of Crisis Text Line, a nonprofit that offers free counseling for people in crisis. Early-childhood education, she declared, is one of the most dignified ventures that entrepreneurs and investors can be a part of, one that deserves proper financial support.

Yet this sector suffers from under-investment—even though these services are often critical in pinpointing and addressing development problems later down the road. Investing in programs and services during one’s most formative years, Lublin added, can help parents and educators better understand children’s development needs before they start formal schooling.

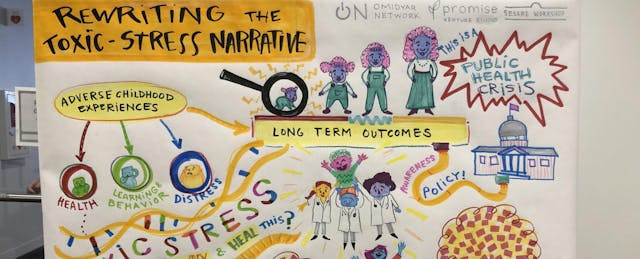

Lublin was one of many voices at the conference who sought to shift the perception that caring for children up to age 4 is solely the responsibility of the individual families. That message was reinforced by pediatrician Dr. Nadine Burke Harris, who is also founder and CEO of The Center for Youth Wellness. Echoing themes from her popular 2014 TED Talk on childhood trauma, Harris shared her latest research linking adverse childhood experiences to developmental delays, academic struggles and even chronic illness.

Harris’ advice for entrepreneurs and investors: Any venture that hopes to make meaningful and lasting impact in supporting early-childhood development must be well-versed in the medical and educational communities, as both fields are undoubtedly interconnected.

Supporting early-childhood development also requires new strategies, interventions and metrics, said Dr. Jack Shonkoff, the Director of the Center of the Developing Child at Harvard University.

Citing findings from his recent article, published in Pediatrics Journal, he claimed that over four decades of research has shown that while early-childhood interventions can produce positive outcomes in a child’s health and brain development, these impacts are typically moderate and ineffective at scale. That’s partly due to the fact that previous research relied heavily on defining “evidence-based” interventions as those that worked for the mean average of the participants in the study. But this narrow definition of efficacy obscures what may be working exceptionally well for some children, and poorly for others.

Shonkoff argued that breakthroughs in other medical fields offer inspiration for how early-childhood research can be more effective. In the neurosciences, findings in neuroplasticity and how stress shapes human development should inform how researchers design and test new interventions. He suggested that the medical and education fields redefine the criteria for determining whether an intervention is “evidence-based” to also account for children who fall outside of “average.”

Early Entrepreneurs

Alongside researchers, nonprofits and startup entrepreneurs also took to the stage. Below are a few standouts from more than 50 organizations that shared their efforts to help parents, children and caregivers tackle a host of factors that are critical to one’s upbringing.

Poverty: Impoverished communities usually lack basic educational resources that are important to a child’s development. An Ohio-based nonprofit, The Conscious Connect is redeveloping vacant lots, abandoned spaces and other “book deserts” into places that provide children with access to culturally-relevant books. EMPath Economic Mobility Pathways, a Boston-based nonprofit, aims to apply brain science to its mentoring service that helps low-income people reach economic independence by providing coaching in health, family life, finances and education.

Social development: Strengthening social emotional skills is often integral to preparing children to live, grow, and thrive in the world around them. Better Kids, a New York-based startup, has developed lesson plans and games that aim to help children understand their own emotions.

Screening for developmental delays: A common theme throughout the two-day event was a call-to-action for better and more accurate tools to help parents screen for potential developmental issues. That got a couple companies perked up. San Francisco-based BabyNoggin offers a mobile platform that lets parents and pediatricians screen for developmental delays, and helps them obtain referrals if intervention services are needed. Reflection Sciences, based in St. Paul, Minn. offers an early-learning readiness assessment that focuses on helping children strengthen their executive functioning skills.

No San Francisco tech conference is complete without pitches that raise eyebrows. BrainChild Technologies is working on a “smart pacifier” that can help parents measure their infants’ developmental progress based on their sucking behavior. The company recently won a grant from the National Science Foundation to explore whether this pacifier can help adults track early signs of autism spectrum disorder.

Childcare marketplace: Depending on where a family lives, finding a qualified and trustworthy childcare provider can difficult. In recent years, a gaggle of startups have emerged to create marketplace listings to connect childcare providers and parents. MyVillage and Wonderschool are two companies that provide aspiring childcare providers with the resources, training and professional network they need to run in-home childcare programs. Their aim is to increase the supply of qualified providers, especially in “childcare deserts” where few such services exist.