This is the final part of a three-part series looking at how one college in Texas staged a turnaround. Read part one and two for background.

TEXARKANA, Texas — The road to success is often winding.

In the case of one community college in east Texas, achieving its goals required more than just a shiny new education technology tool.

For this two-year school, Texarkana College, it also involved a local billionaire benefactor, community members rallying to support the college as it faced bankruptcy, and an overhaul of curriculum and advising from within.

For all of the progress that Texarkana College has seen, however, major issues persist. In 2012, the graduation rate for men and women was 7 and 16 percent, respectively, according to data from the National Center for Education Statistics. In 2016, men’s graduation rates spiked to 38 percent, while women’s graduation rates increased much more slowly, to 26 percent that same year.

Students taking time off of school or switching to part-time schedules to take care of young children are two reasons why.

That’s been the case for students like Tiffany Wills, a full-time student studying to be a dental hygienist, and a single parent. “I'm able to take classes, but the workload of homework can be overwhelming sometimes,” she says. What gets her through it, she adds, is “a lot of help from my parents, and a lot of prayer and faith.”

Some of Wills’s friends have taken time off from their studies when they have kids. She took a whole semester off herself. “I felt like I was taking away too much time with my child, so I took a semester off and focused on her, and got myself back together and got refocused.”

Wills is a local, but she didn’t always see Texarkana College as the place she would end up. She knew about Texas A&M—Texarkana, but the university was too expensive. But she’s found support on campus, through tutors, and through an unlikely bond with other students she’s met who are in similar situations.

“It's a lot different than what I thought because everybody here has different challenges and different backgrounds, different upbringings, but you almost know that each student is almost struggling, in a sense,” says Wills. “You meet people who you don't think you would click with, but because you had something in common, it brings different backgrounds together.”

Shelby Albury often frequents the college cafeteria to study and get work done before heading home to her husband and two kids. Settled in the cafeteria with notes spread across the table, she says she’s also had friends who dropped out of their program at the college when bills and family responsibilities became too much to bear on top of studies. “Sometimes you have to make a choice between bills and school,” she says. “Electric companies don’t understand, ‘I need to go to class.’”

Officials at Texarkana say the college has made progress changing the internal culture on campus. But changing the school’s reputation in the city is slower going.

Texarkana’s other major anchor institutions are prisons. A federal prison and privately-operated county jail are located within six miles of the college. A juvenile detention center sits at the town’s center, just across the state line in Arkansas.

Albury says she’s concerned about her kids growing up and seeing jail as a normal, or even likely, option for their future. And she’s trying to show them something different. “A lot of people in my family didn’t go to college and had dead-end jobs,” she says. “I want to show my kids that no matter what age you are, you can succeed in life.”

Both students say what they do like is that the school has a tight-knit feel. On campus, Wills says what’s helped her is the ability to find support when she needs it from faculty advisors or tutors on campus. “Everybody's so helpful here,” says Wills. “I just met with a tutor, and I met with her on Sunday. I'm probably going to go with her before I take the test today. She has helped me a lot.”

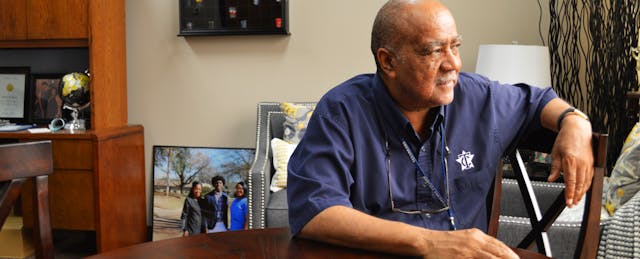

Robert Jones has witnessed these struggles in his 28 years at Texarkana College, where he teaches math in the morning before stepping into his office as Dean of Students.

“Our students bring a whole lot of issues with them,” he says. “Not only do they not have any money, they don't even have anybody they can go to and get some money.” Those problems include student grievances, disciplinary issues and bigger life challenges that he often finds students coming to him with.

Jones says he's particularly proud that the college has increased graduation rates among black students, going from from 5 to 22 percent from 2008 to 2016. But an achievement gap still persists when compared to white students at the college, whose graduation rates went from 9 to 38 percent during the same time period.

Jones also says he sees many black male graduates concentrated in technical fields, more so than their white peers. “They come in, learn how to do air conditioning, learn how to do welding. You go in those classes and they’re something like 70 to 80 percent black men,” says Jones. “I'm sitting up here and saying, ‘I don't even hardly see that many African-American males on my side of the campus.’”

Moving Forward

These days, students at Texarkana College can be seen coming in and out of the library. There’s a new media facility for the college radio station, and a revamped academic commons space. Instead of a tone of resignation, administrators gush with pride about where the college is headed.

Donna McDaniel, vice president of instruction at Texarkana College, knows there’s still much work to be done, though. “We need to improve in every area,” she says. “We need to improve with our academic support. I feel like our enrollment services could still be better. We keep tweaking it and fine tuning it.”

But who will be leading those future initiatives remains to be seen. In September, Texarkana College President James Henry Russell announced that he is leaving the college in January 2019 to re-enter the private sector as chief financial officer for agricultural supply distributor BWI Companies. After joining the college in 2011, Russell helped lead a campaign to pass a local ballot measure that prevented Texarkana College from bankruptcy and closure.

“It is hard to beat the feeling of a [Texarkana College] graduation when you see our amazing students graduate after conquering and pushing through so many life issues and struggles to get to a better place in life,” Russell said in the school’s announcement of his departure.

“The TC staff continually takes on more roles and responsibilities than ever in the history of the college, and they do it with smiles on their faces and the best customer service of any organization around.”

Financial struggles aren’t wiped away yet, either. In 2017, there was a proposal to increase the tax for Texarkana College from approximately 11 to 12 cents per $100 of assessed property value, the Texarkana Gazette reported. The increase passed, but not without grumbling from community members.

“I am for higher education, but not at the expense of Bowie County citizens. We have a public school system, kindergarten through 12 that we have to support. It seems that TC is like a money pit,” one resident said at a public hearing about the tax.

The fact that uncertainties lie ahead at Texarkana College is something Jones has come to terms with. But he’s comforted by the fact that he’s seen the college start over again.

With this next transition, he has hope: “For us to survive, we're going to have to be turning out a good product. We're going to have to make sure that a large number of these folks come in, they get out, and no one department or one program can do that. We've all got to get out here and talk to these students and work together to make this happen.”