It was the final day of Bike Zambia program. Along with 35 fellow riders, I was attending a Grassroot Soccer tournament. Grassroot Soccer is an organization that uses soccer to get into the communities to educate kids about AIDS & HIV.

We watched a tournament where some of the young players had cleats and others did not, and there was a tent set up where kids could get tested to find out their HIV status. On the sidelines, kids of all ages were hanging out, dancing, kicking soccer balls and engaging with our gang of tired and smiling riders.

I was particularly enchanted by a gaggle of young girls who were dancing. One of these girls was a wild-haired, 9-year-old named Gladys. She and I found a connection with each other, and she soon invited me to sit down with her on the sidelines. After we sat, we were soon joined by her group of friends who sat in a circle and taught me a variety of patty-cake style games. One of these games (we must have played at least six different ones) begins with the group reciting together: “This is a game of concentration, no repeats or hesitation…”

It’s a game that I’ve played with my own nine-year old daughter. Just as nine-year-old girls on either side of the world play the same games, education systems on either side of the world face similar challenges—in particular, how to think about educating the whole child, to grow and flourish, absorbing both academics and the other life-lessons they will need.

That wasn’t the big revelation I expected to have when I signed up to spend my summer vacation cycling 325 miles across Zambia to raise money for HIV education and prevention and women’s economic empowerment. My expectations for the trip were more focused, candidly, on what I felt I would take away from the experience—something around what I could learn by pushing my physical limits way beyond what I thought possible, to what I might discover if I had two glorious weeks away from the daily responsibilities of cooking for my own family.

First, however, I had more prosaic lessons to absorb, including how to:

- raise at least $4000 that would be a charitable donation for HIV education in Zambia (a trip requirement);

- train to handle the intense biking (78 miles on a mountain bike on dirt roads and sand in one day is really hard!);

- find someone who would take care of my kids while my husband and I were away;

- disengage from work! (I run sales at EdSurge).

I succeeded on most fronts: I raised almost $5000 (thank you supporters), I rode all but 12 miles, and friends and family offered to look after my kids (thank you to the Knight family and my father-in-law!) But I couldn’t seem to not think about work, or at least educating the whole child, a huge theme in the office as we prepared for our fall conference.

On the first day of Chooda’s biking & fundraising program, we visited the World Bicycle Relief Zambia headquarters where we heard from Brian Moonga, WBC’s country director, and Mrs. Chilufya Mwaba-Phiri, executive director of ZHECT (Zambia Health Education & Communications Trust). ZHECT’s primary goal is to educate and prevent the spread of AIDS in Zambia, where 1 in every 8 adults is afflicted. Normalizing how everyone talks about HIV and educating girls are important keys to making this happen. Schools not only provide academic education, but also an environment where information about AIDS and HIV can be shared.

In partnership with ZHECT, World Bicycle Relief distributes sturdy Buffalo bicycles to healthcare workers so they can see more patients, and to students for commuting to and from school. Bicycles make an incredible difference in a country where 78 percent of residences are more than 3.5 miles from a secondary school and very few people own cars. I saw no buses traversing the dirt roads we rode between the thatch-roofed hut villages later on.

It was fascinating hearing about how these two organizations partnered and supported each other. Moonga and Mwaba-Phiri talked about the challenges of giving girls equal access to education in a culture that puts the onus of housework on females. Daughters are responsible for making the fire, preparing the breakfast and cleaning up afterward, while their brothers just get up, get dressed, eat and walk to school. The heavy chore list means that girls leave later for class than their brothers. So when a girl gets access to a bicycle, she can still make it to school on time.

This is a perfect example of how one needs to think about a community’s culture in order to set its children up for success. These organizations realized that they would not be able to change the culture, but they were able to find a way to work within existing cultural norms to help girls get equal access to education by prioritizing girls receiving the donated bicycles (70 percent are given to them). This talk helped set the tone and purpose of the trip, which consisted of riding our own (fancier) bikes through Zambian villages and camping along the way.

As our group of riders cycled through the back roads and thatched roof villages, we saw numerous “Zambia Ministry of Education” signs which signaled that a school was nearby. Each one of these signs had an AIDS ribbon painted on it. I was reminded of the work that ZHECT was doing to work within the school system to educate kids about HIV & AIDS. The statistics suggest impressive progress has been made: New infections in babies have been brought down to almost zero, and over 65 percent of adults have been tested.

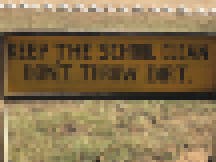

Each day of our bike trip, during our morning stretch and pep talk, we were reminded that this ride was not a race, and that we should stop and engage with the people we saw along the way. On our first day of riding, the first rest stop was at a school. Unfortunately, class was not in session but we were able to walk around the campus. There were painted messages all over the buildings and playground saying things like “Keep the school clean; Don’t throw dirt” (the campus grounds were all dirt), and “Learning while playing” and “Let us educate our future.”

I couldn’t help but smile as I thought about how these messages were similar and different from the posters we see in American classrooms featuring kitties hanging from branches that read “Hang in there.” A crew of village kids did venture onto campus to check us out and a fun time was had as the two groups explored getting to know each other, as much as one can during a 30-minute rest stop.

As our ride continued over the following six days, I paid particular attention to the Ministry of Education signs. It seemed like there were schools every 15 miles or so, which makes sense when you consider that the kids are walking to school. At another school campus where some of us stopped later in the trip, there was an eye-popping painted image and sign on the side of the “Sanitation Corner” wall. It featured a simple painting of a child defecating and read “No open defecation. Always use a toilet.” It’s not a message one would encounter in American schools, yet the focus on cleanliness reminded me of how sanitation is something we sometimes take for granted when it comes to a child’s development and education.

I would have liked to visit a school that was in session to see other aspects of what education looked like in Zambia but that was not the focus of this trip. Throughout the journey, we had hundreds of schoolchildren greet us at the side of road, waving with unbridled enthusiasm and gigantic smiles shouting “Hello! How are you? I am fine,” which was an incredible inspiration as we logged some beautiful (but painful) miles in the saddle.

I returned home filled with the joy of having accomplished something both meaningful and challenging and I’m now scheming how to give my daughters a similar learning experience by bringing them to Zambia.