They go by names like littleBits, Makey Makey, Squishy Circuits and Makeblock, and their goal is to get kids thinking like inventors instead of passive learners. Aligned with the maker movement—which focuses on using hands-on activities like building, sewing, assembling and computer programming for learning—the kits provide a foundation that teachers can use for guided projects both in and out of the classroom.

But are pre-packaged kits really in the spirit of the maker movement, or are they just leading students down a narrow path without allowing them to be truly creative, inventive and genius?

Sylvia Martinez, co-author of “Invent To Learn: Making, Tinkering, and Engineering in the Classroom,” says the answer to that question depends on the kit itself. “There’s kits and then there’s kits,” says Martinez. “I think there are definitely some that are more open-ended than others, and that offer a baseline for the teacher or parent who purchases the kit in order to help their child complete a [project].”

Having a set course down that path can be especially useful for the teacher who isn’t tech-savvy, or who needs a consolidated selection of parts to work with (versus having to pull together those parts individually). But moving to the next level on the makerspace ladder—often more open and exploratory—is also important. “A lot of teachers will then graduate after doing, say, 10 different kit-based projects,” says Martinez, “and realize that they probably don’t need hundreds of the same kits for the next school year.”

Martinez says teachers who use kits can also get creative when using them in the classroom. By hiding the directions and/or the box (which usually features one or more photos of the completed project), for example, teachers can encourage kids to think on their own. “You can kind of steer kits that are very rigid away from that rigidity,” says Martinez, “by doing some creative things.”

Thinking on Their Feet

It’s not unusual to see students in grades 3-12 at Rapides Parish Library tooling around with 3D printers, virtual reality glasses (VR) and other advanced technology. Some of the Alexandria, La., library’s makerspace materials come from a retired teacher who volunteers his time and brings his own materials with him, but the balance of the supplies are kit-based.

“We’ve done it both ways, and have found that unless you have years of experience working with students and with technology and science, putting together makerspace projects can be quite difficult,” explains Tammy DiBartolo, youth services and outreach coordinator.

“In my experience, it's better to have the kit because then you know what you have and what to plan for,” says DiBartolo, who tells teachers to consider their own resources and experience levels when deciding on the best makerspace approach. “I thought it would be easy to put a bunch of stuff out there and let the kids do it themselves,” she says, “but some students aren’t good at thinking on their feet and tend to get frustrated.”

But Where’s the Productive Struggle?

As director of the SMU Maker Education Project, Katie Krummeck says that while pre-made kits do an “admirable job of trying to develop projects that require more complexity,” the ultimate goal of the makerspace should be to get students working with real-world materials and tools. More importantly, it should push kids to solve their own problems instead of giving them a pre-determined path to explore.

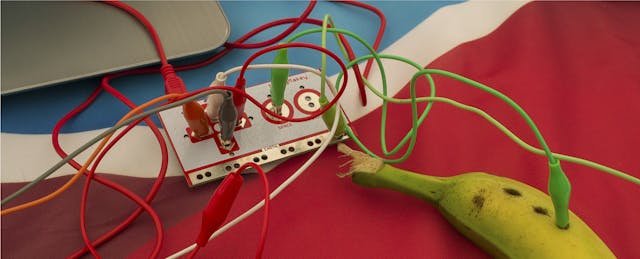

“I think that those products are wonderful to get people started,” Krummeck says, “but one of the limitations is that because they're really well-designed products, they essentially take the opportunity for productive struggle out of the product themselves.” For example, she says littleBits’ color-coded, magnetized electronic building blocks “eliminate some of the failure and struggle that we actually really want to see in maker-based learning experiences.”

Ideally, as the makerspace concept advances, Krummeck says the student's capacity for learning more complex and technical ideas will advance. Put simply, while a pre-assembled kit can serve as a good starting point, it shouldn’t be the end-all.

“You eventually want to move toward using raw materials, tools and materials that you would find in a professional fabrication lab,” Krummeck notes, “with the ultimate goal of building the technical proficiency and confidence in students that they're using tools that are not predesigned to be user-friendly.”

Let Them Play

In her role as librarian at Stockwell Place Elementary School in Bossier City, La., Kim Howell oversees two different makerspaces: an old-school maker lab where kids do hands-on project with original materials and a studio that features more advanced technology. To populate the former, Howell challenged all 400 students to bring to school something they thought was cool in a Ziploc bag. “I used all of those materials to build our maker lab,” says Howell. That initiative started with no technology at all—just a bunch of Play-Doh, Legos, paper, pencils and common household items.

Howell says she instantly saw the value of the makerspace when students struggled to make a chain out of paper. “Some kids shredded the paper, and some cut the paper into two pieces,” says Howell. “It’s like they didn’t have any experience using scissors, and it made me realize that we need to build some self-confidence and resiliency with using tools they’d never even explored; and just let them play.”

When Stockwell Place Elementary built its second makerspace four years ago, it started using kits from Circuit Cubes, Lego Robotics, and Makey Makey, among others. Howell says the two spaces complement one another in that one encourages hands-on creativity while the other helps students get hands-on with higher technology.

For teachers, having a kit helps to simplify the lessons and gain easy access to the necessary parts and pieces—a plus for instructors who aren’t STEM specialists. “I’m an English major, so if someone said ‘Hey, you’re going to have to teach a coding class tomorrow,’ it would very overwhelming,” says Howell, who notes that while high school teachers may already be tech-savvy and don’t necessarily need a source of maker materials, kits definitely have a place in the elementary environment. “Our teachers love them.”

It Won’t Do the Teaching for You

To schools and teachers deciding on the best approach for their own makerspaces, Krummeck says it’s important to factor in the mission of the space itself. For example, are kids coming in to just tinker around, or are there specific instructional goals in place for it? Don’t be afraid to start up by using pre-made kits that help students get some traction, she says, but as the space develops you’ll want to come up with new ways to help students develop technical and creative proficiency.

“At that point, the user-friendly products become less useful,” says Krummeck, “because they do [put up] barriers to students developing that technical proficiency (e.g., they can’t see inside of the boxed product to understand exactly how it works) and don’t enable the richest possible learning experience.”

Martinez concurs and says depending on a kit to create an open-ended learning environment isn’t the best approach. “As part of an educator trying to gain experience with materials, kits can be really useful, but it's a step on a path,” says Martinez. “The kit isn't going to do the teaching for you.”