Follow education technology-reform projects, and you’ll find mixed academic outcomes and expensive consultants.

Take Fulton County School District, in Georgia. In July of 2015, the district paid more than $400,000 for alignment, strategy and professional services from Education Elements, a for-profit personalized learning consultant, according to receipts obtained by EdSurge from the district. Later that year, the district paid an additional $215,500 more for “professional services.” In less than two years, between 2015 and 2017, the district paid more than $4.5 million to the firm for personalized-learning consulting services.

School districts around the country are adopting personalized learning—a pedagogy often described as a way to encourage learning that is individualized, differentiated and student-driven through technology. To help teachers implement the learning model, schools and districts are increasingly paying top-dollar for specialized consultants. But those investments don’t always pay off. At Fulton and other districts looking to consultants, academic achievement dipped in some schools after the changes made with input from the consultants.

Now, some educators—and consultants—are calling for edtech consulting firms to be held accountable for whether or not their million-dollar advice translates into improved, measurable learning outcomes.

“This notion that consultants provide the technology, the input, the recommendation—all the good stuff—and then it’s up to the organization and managers to implement and consultants take no responsibility. What a great game that is for the consultant,” says Ron Ashkenas, an author and partner emeritus of Schaffer Consulting. “It may sound like a radical idea, but it makes so much common sense. If you are proposing something that isn’t going to work, then no matter how great it is, it is wrong.”

Turning to Consultants to Parse-Out Personalized Learning

The concept of using technology to personalize the learning experience has been gaining appeal among educators seeking solutions in struggling schools. In fact, a recent survey of 500 school leaders noted that 54 percent see the concept as a “promising idea” or “one of many school improvement strategies.” But a lack of clear definition or understanding around what personalized learning is, exactly, has made it difficult for educators to envision and implement the practice. For some, the model is centered around adaptive technology that students use independently to drive their own learning. But for others, the teacher is still central to the picture, using technology as a means to support differentiated instruction.

That uncertainty is causing some educators—the ones with funding—to turn to high-priced consultants for answers. School leaders hope that the support and understandings shared by people they view as experts will help teachers learn how to perfect personalized-learning instruction.

For researchers keeping their eyes on the education-reform sector, this scene is familiar. Ambitious district officials flush with funds from philanthropic donations, grants or special tax revenues take on big projects. As soon as the money pours in, much of it ends up in the hands of consultants offering expert advice to school officials.

One high-profile version of this type of event occurred in Newark back in 2010, after Facebook billionaire Mark Zuckerberg gave a matching $100 million-dollar donation to the New Jersey school district. Consultants charged the district as much as $1,000 per day for their services, as recorded in former Washington Post reporter Dale Russakoff’s book, The Prize. In the end, $21 million dollars went to consulting work. But when schools didn’t see the results of their reforms, implementing the strategies and recommendations consultants gave, the frenzy of experts surrounding Newark seemed to dissipate.

Consultants Debate Accountability

Some consultants think they shouldn’t have to bear the accountability for what schools do with their advice. Anthony Kim, CEO of Education Elements, argues that he can’t make promises about academic results.

“Of course everything is driven by student outcomes, but do I think that Education Elements is responsible for those? Probably not,” says Kim, in an interview with EdSurge. “Probably not because we're not there every day providing the instruction.”

Kim says he judges the firm success based on how successful the schools “feel,” and that could vary depending on who responds to their surveys or solicitations for feedback. Traditionally, he notes, management consulting companies help districts set up strategic plans but leave the implementation process to teachers. His company coaches educators through the entire implementation process seeking feedback for iterations until about 18 months after the projects start.

“You don't just go to a coach once, and then you’re like, ‘hey, I just spent an hour with you. You go and do your stuff.’ Coaches deal with feedback from the people that they're working with,” explains Kim. “We make some recommendations based on what we see in the market. We're constantly getting feedback from them on what's working and what's not for them. And we're adjusting to that. It's a series of iterations.”

But Ron Ashkenas says what Kim offers is not enough. He argues that it is time for school leaders to demand more accountability from consultants—particularly those leading education and technology reforms.

“The right recommendation that can’t be implemented properly is the wrong recommendation,” says Ashkenas. “If you are giving a school a technology that they cannot use—or it is not really going to make a difference in reading scores or school performance—then it is not the right input, not the right system. Obviously, the big consulting firms don’t like that idea because they have a vested interest in selling by the pound, hour, recommendation, but not by the results.”

Ashkenas says he has seen several grandiose technology overhauls where consultants charge large fees for impacts that can’t be measured until several years in the future. And he thinks that timeline helps alleviate consultants of all accountability, especially when a school’s staff and leadership change.

Particularly in school districts with wildly different variables from campus to campus, he says leaders should be wary of anyone who promises a scalable solution without measurable results in the near and distant future.

“Ask the consultant, ‘how will we know this is successful?’ How will we know in the short term, not just in the longer term? What are some indicators in 30 days, 60 days, 100 days and six months that we should be looking for?” explains Ashkenas. “If there are no indicators for two years, that is a prescription for disaster.”

By indicators, Ashkenas does not mean milestones such as collecting data by a particular date. Instead, he is referring to things like teacher proficiency with instructional styles or technology that yield measurable improvements in students achievement. For example, one consulting group he works with called Say Yes To Education, which measures success by improved graduation rates and other indicators, offers students who graduate from the high schools they work with money to go to college. This is what Ashkenas describes as asking consultants to put some “skin in the game.”

Ashkenas says school leaders should be direct in asking consultants what they are accountable for. Pose questions like: “Would you be willing to put your fees at risk to make sure that this works and we get the results we need?” he adds. “If the answer to that is ‘no,’ well why should schools put all their resources at risk?”

A Tale of Two Personalized Learning Reform Efforts

In Fulton County, school leaders thronged with cash from a special tax the city issued sought to pursue the promise of personalized-learning by contracting with Education Elements.

When asked via phone and email why the district chose to contract with Education Elements and did not seek guarantees for improved academic outcomes, officials did not issue a comment. If the district did require measurable improvements from consultants based on indicators such as the percent of students reading on grade level, the outcome would likely be mixed.

The large district, with about 110 schools, went through a rocky personalized-learning implementation process with the consultant group, where educators struggled with fractured understandings of the model, and test scores fluctuated in certain schools. EdSurge analyzed data from the state report card on every elementary school in the first personalized learning implementation cohort.

Across the district, third-grade reading levels have fluctuated dramatically throughout the period. Elementary schools like Mountain Park, Shakerag and Liberty Point, for instance, steadily increased, while Medlock Bridge, Dovin, Randolph and Lake Forest ended with lower performance than when they started the implementation.

Other districts without guarantees for positive, measurable results have also seen mixed outcomes from their personalized-learning reforms. In 2011, the Charleston County School District (CCSD) in South Carolina, the second-largest in the state, launched what they called “Vision 2016”—a five-year plan to close the achievement gap and raise graduation rates.

One of the major components of this reform was enacted in 2012 when the district received $19.3 million in Race-to-the-Top grant funding from the federal government. According to the grant application, the funds were going to be focused in 19 low-performing schools, three high schools and 16 middle and elementary feeder schools. The middle and elementary campuses would take on a personalized learning pedagogy so students would be prepared when they entered the tech-heavy high schools.

The district contracted with a technology provider called Threeshapes, an education nonprofit called Communities in Schools and a consulting group called Marzano Research Labs.

“The goal was to build the feeder pattern to get kids, with an emphasis on personalized learning, prepared for a high school that was technology integrated slash personalized learning,” says Anne Wyman, an instructional coach in CCSD’s Department of Innovation and Digital Learning.

The district’s contracts with the consulting group provided them with coaches to help lead personalized learning, collect data on progression and offered teachers feedback on their work based on the data. The district paid Marzano Research Labs at least $1,820,880 between January 2014 and June 2016, according to public records analyzed by EdSurge.

Overall, Wyman says she appreciated the coaching she received from the consultants, saying it helped her become a better teacher. But she also feels there was a disconnect between the progress the consultants told her the school was making after they conducted classroom observations and the actual results she was seeing.

“I would say things like, ‘I am really shocked we did that well on our [school observations]’ and other people would be like, ‘well, just celebrate it,’” explains Wymann, noting the conflict between the positive feedback from consultants and dropping test scores her school was experiencing. “But I didn’t know if there is a celebration to be had when other data like test scores didn’t corroborate with their data.”

Wyman’s intuition was affirmed by student outcomes that year. In 2016, when the state department of education rolled out new exams meant to capture college readiness, the big vision of personalized learning seemed to turn into a mirage.

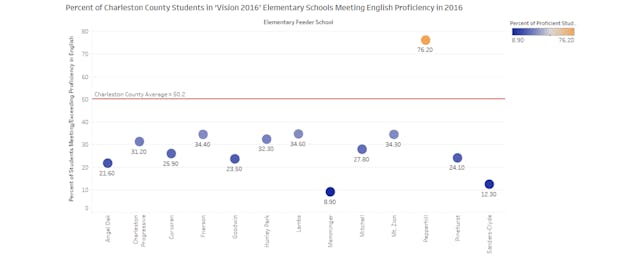

Several schools across the state saw decreases in achievement, but most of the feeder schools who had been undergoing a personalized-learning transformation in Charleston County saw their achievement levels plunge. Schools like Memminger Elementary had as few as 8.9 percent of students showing proficiency on English exams, significantly lower than other schools in the county that averaged a 50.2 percent proficiency level in English.

“The point where we were starting to get that year-long data back was right when things were starting to crash,” continued Wyman. The district also went through an audit that year revealing an $18 million-dollar budget deficit. And several staff members were fired or quit.

Looking back, Wyman says that after millions of dollars in consulting fees, the reforms don't feel like a success. “I find myself still waiting for the fruits of our efforts to emerge,” she continues.

She recently received a notice from the district listing nine failing schools that the state department of education is threatening to take over if they don’t show improvement. Wyman says that seven of the nine schools on the new list were part of personalized-learning reform efforts since 2012.

The district ended its contract with Marzano in 2016, and it is now working with Education Elements in certain campuses, with the support of federal grants. So far school officials have spent at least $1,260,000 with the firm between June 2016 and March 2018 according to public records EdSurge reviewed. Wyman notes that she feels better about the shift but still wonders if school leaders are asking for any assurance that they’ll get results from the changes suggested by the new consultants. It’s possible, she says, that the money could be better spent on things like advanced degrees for educators or on reducing class sizes.

“With Marzano, I don’t believe there was any type of ill intent or conspiracy,” says Wyman. “We want to celebrate growth, but at the same time, if we are paying them to collect and analyze data, I need to know whether or not this is working.”

Regarding her district’s latest contract with Education Elements: “They have some good information and all of that,” says Wyman. “But it is all soft data. If you read the contract, they are not held accountable for growth. And that’s a lot of money.”