Economists following the teacher protests in Oklahoma, West Virginia, Kentucky and Arizona say they saw this coming. As the costs of living, higher education, healthcare and retirement are rising, researchers studying salary trends note that the average pay for teachers has dipped.

“That’s a really bad situation to be in, being asked to pay more as your pay is actually declining,” says Dr. Sylvia Allegretto, an economist at the Institute for Research on Labor and Employment at the University of California, Berkeley. “In real terms, meaning after you adjust for inflation, the average U.S. teacher today makes $30 less a week than they used to.”

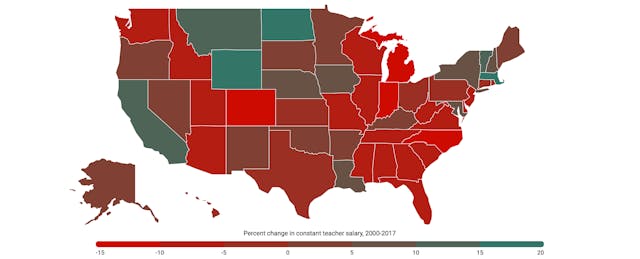

According to data from the National Education Association (NEA), constant pay for educators— meaning pay adjusted for the cost of living in each state as determined by the Consumer Price Index—in some states has decreased as much as 15 percent between the years 2000 through 2017. An educator living in a place such as West Virginia (where teachers went on strike in March) makes about 9 percent less today than they did back in 2000.

In states such as Michigan, though the average teacher salary may appear higher than the national average, the constant pay actually declined due to other cost-of-living indicators in the state.

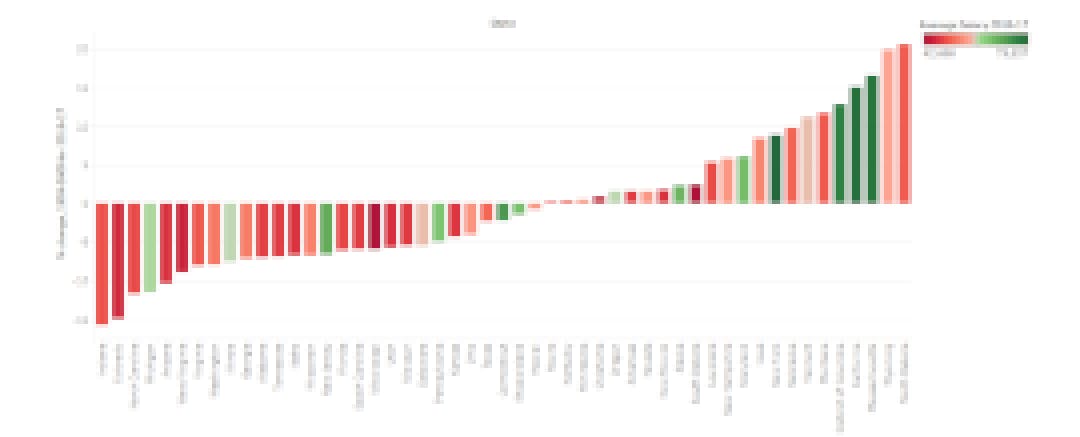

| States where constant teacher salaries declined the most from 2000 to 2017 |

Percent change | States where constant teacher salaries increased the most from 2000 to 2017 | Percent change |

| Indiana | -15.72 | North Dakota | 20.59 |

| Colorado | -14.98 | Wyoming | 19.90 |

| North Carolina | -11.76 | Massachusetts | 16.53 |

| Michigan | -11.52 | California | 15.17 |

| Arizona | -10.38 | District of Columbia | 12.83 |

Comparing Teacher Salaries to Other College Grads

For economist Allegretto, these trends in pay declines are troubling, particularly when she compares the salaries educators make to that of other college grads. Her research, based on data from the Federal Bureau of Labor Statistics, indicates that while educator pay has declined about $30 a week, the pay for graduates in other professions has increased approximately $124 a week. This difference in pay is what Allegretto calls the “teacher pay gap.”

“Why would you want to be a teacher when you know teacher pay is actually declining over time?” asks Allegretto. “This is really a terrible confluence of policies and events that are coming together because it means our best and our brightest are probably not going to want to be teachers in this country.”

Note: "College graduates" excludes public school teachers, and "all workers" includes everyone (including public school teachers and college graduates). For more details please see the report.

Allegretto has been tracking the teacher pay gap for years. She notes that although the gap between male college graduates entering teaching and those choosing other professions has always been high (around 20 percent), the gap between women coming into teaching careers has flipped from a positive 4.2 percentage points in 1979 to a negative -13.9 percentage in 2015.

“If you were a teacher back then you had a positive pay gap,” says Allegretto, meaning female college graduates going into teaching made more than their peers in other career pathways. She elaborates, explaining that in the 1960s—when it was difficult for women to access professions not considered “pink-collar” work such as nursing and teaching— many highly qualified women became educators. “Teachers did a little bit better than other professions then.”

Within Allegretto’s research, she also notes that the states where teachers are protesting tend to have higher pay gaps. Arizona, Oklahoma and West Virginia have pay gaps larger than the national average. Arizona has the most substantial teacher pay gap in the country.

“Teachers in Arizona make about 63 percent what other college grads make, that's a huge gap,” explains Allegretto. “It is not surprising that these are the states that you are seeing a lot of this activity. These teachers know that they are falling further and further behind.”

Does Being In A Union Help?

On an NPR interview earlier this week, Randi Weingarten, president of American Federation of Teachers, noted from the grounds of an Oklahoma teacher protest the possible correlation between discontentment with wages and collective bargaining rights saying, “You're going to see more and more and more of this because the states that have collective bargaining, they work this out at the bargaining table.”

Speaking on the Janus v. American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees, Council 31 case—a complaint currently being argued in the Supreme Court—Weingarten noted that the ruling could weaken the collective bargaining power of unions across the United States.

Many states with unions require workers to pay member dues even if employees are not union members. The logic being, those non-union workers receive indirect benefits such as salary increases and health care from the bargaining representation unions do. The Janus case, if ruled in favor of the plaintive, would make it illegal for states to require non-union members to pay union dues. That could put a dent in union budgets and effectively make all states "right-to-work" areas.

Several states have already adopted right-to-work laws or regulations that allow employees to decide whether or not to join or financially support a union.

Looking at constant salary data from the NEA and cross-referencing that with information from the National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation, an organization that tracks which states have right-to-work laws, it is unclear whether such laws have a direct impact on compensation. Yet, it is interesting to note that most states paying salaries higher than the national average, set at $58,950 by the NEA, do not have right-to-work laws. Michigan is the exception to this observation with an average salary of $62,200.

In Allegretto’s research on teacher pay gaps (comparing college graduates who enter the teaching profession to other professions), she concludes that overall the pay gap for teachers in unions is smaller than the gap for non-union educators.

“Being in a union does not protect you from a pay gap, but it helps make the gap smaller,” Allegretto explains. “Both of those pay gaps got worse over the period, whether you're in a union or not and that is because they are making it harder for teachers to collectively bargain.”

Pointing to laws in places such as West Virginia that ban collective bargaining activities like striking, while also issuing right-to-work ordinances, Allegretto makes the case that simply having unions in the state is not enough to ensure equitable pay for educators. Several state laws impact the rights of union workers, and the federal Janus case is expected to have a sweeping, weakening effect.

These changes, Allegretto notes, could cause salaries to continue to slide, possibly impacting the caliber of applicants seeking to join the teaching profession.

“The future of this country hinges on the shoulders of our teachers being very good and effective,” says Allegretto. “That is the big picture.”