I always enjoy lesson planning in public places, mostly because it keeps me from binging on the latest Netflix series. In December 2015, I found myself toiling away on a fifth grade figurative language lesson in a unique place—a local tech meetup called Code For Vegas.

I sat next to my husband as he worked with a team of strangers to design and build a website connecting local veterans with community services. I soaked up all the tech jargon—Slack, Github, JavaScript, recursive functions and deploy. I watched people collaborate to fix bugs and find solutions. On the way home, I relentlessly questioned my husband on the meanings of the new words I had heard.

Teachers are charged with preparing students for jobs that don’t yet exist. What we know is that these jobs will heavily involve coding, artificial intelligence and iterating on user experiences. As I sat at the meetup, I found myself asking: How can I prepare a generation of students for these in-demand skills if I have limited experience with them myself?

In the months that followed, my husband started developing his own web application and I wanted in on the startup grind so I asked if I could participate in some way. I didn’t have the technical know-how to code the site, but as an instructional coach and leader of my school’s behavior support team, I did have experience building efficient operations and logistics. So I became a co-founder and head of operations for our startup, Busker.fm, an application that allows up-and-coming musicians to be discovered and played alongside famous acts.

I spent my summer off helping the developers create core values and streamline their project management process in GitHub, a software development platform. I researched different management structures, such as Holacracy, and read about successful team cultures at companies like Netflix and MorningStar. I analyzed user experience interviews to set priorities for the site.

We incorporated our company in Delaware, held meetings as a board and divvied up shares. It was fun, meaningful work. And, like most startups, we died—failing to gain enough users to even consider turning a profit.

My experience trying to get a tech company off the ground gave me a window into the world our students will ultimately face—one that requires an extreme amount of grit, technical skill, savvy and confidence. And contrary to the traditional progression of learning, one that they could succeed in even without a college degree (many coders are self-taught using sites like Free Code Camp).

Busker may not have succeeded as a company, but I took the lessons and skills I learned from the tech scene and applied them to my work as a teacher. I began treating my classroom like a startup.

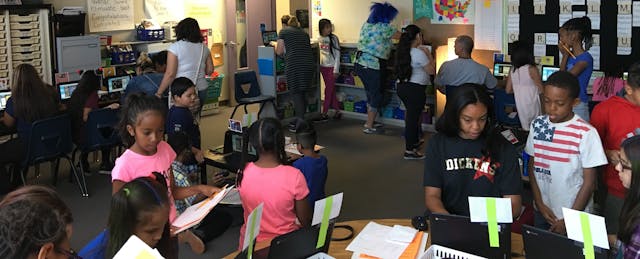

No one in the tech world sits in rows, so I offered flexible seating options from floor trays to wobble chairs to couches.

The CEO of a tech company doesn’t address the whole company to solve every problem, so I ditched whole group instruction in favor of the station rotation blended learning model in order to meet the needs of all of my learners.

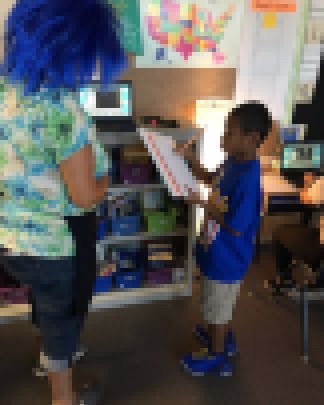

I realized that lessons I used one year ago might not work for the group of learners in front of me today so I modified what I’d learned about user experience and applied it to the learner experience. I tweaked materials, gathered student feedback and iterated on my instructional designs. I saw that I needed to move beyond formative assessment of skills. I needed to ask students whether or not they enjoyed the learning experience—that’s what Apple would do.

Participating in the tech scene also inspired me to create more meaningful projects for my students. Last year, after listening to kids talk enthusiastically about a mobile game called “Animal Jam,” I decided to have my students create their own video games and showcase them at an “arcade” for friends, family and school staff. Not only was this project exciting, it also taught students how to get user feedback and revise their designs. My former self might have seen children simply playing video games. Through my renewed startup lens, I saw 25 Mark Zuckerbergs.

I now teach third grade at the nation’s first school founded by Dr. Robert Marzano. Our school, which opened in September 2017, is a live lab for Marzano’s strategies which include personalized, competency-based instruction with a focus on STEAM and coding. We also teach and assess students’ cognitive, metacognitive and social-emotional skills.

At Marzano Academy, we run just like a fast-paced startup because we are trying to disrupt the traditional model of education. We’re not entirely sure what will work but we value experimentation. Teachers are now “facilitators,” classrooms are “studios,’ and students are “learners.” Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) are constantly being written, tested, surveyed and changed. We have a coding class being taught alongside physical education, music and art. We even use the same tech lingo (deploy, user feedback, iterate and hard stop) that I heard at my first Code For Vegas meetup.

I’ve had to step out of my teacher echo chamber to redefine professional learning for myself. But you don’t have to launch a company to bring the startup culture to the classroom. And with supportive school leadership and an engaged local community, you shouldn’t have to do it alone. Here are some actions teachers, administrators and entrepreneurs can take to bring startup culture into the classroom to better prepare students for the world they’ll be entering after school.