Entrepreneurship is growing in popularity on campuses nationwide as colleges and universities try to cultivate a do-it-yourself culture with courses, clubs and maker spaces. But another trend in higher education threatens to derail young entrepreneurs before they even get started after graduation: student loan debt.

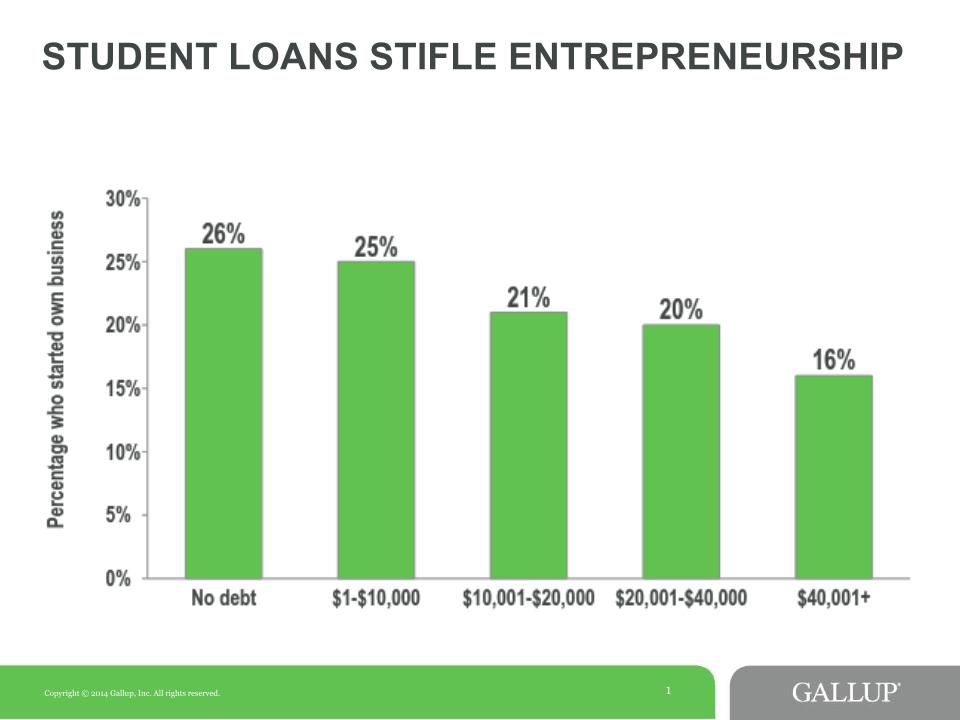

Among those who graduated from college since 2006, 63 percent left college with some student loan debt, according to the Gallup-Purdue Index. And of those, 19 percent said they delayed starting a business because of their loan debt. That proportion rises to 25 percent for graduates who left college with more than $25,000 in loan debt (the average for the class of 2015 was $35,000).

“If you have debt, you’re less likely to take risks after graduation because you have bills to pay,” said Brandon Busteed, who heads up Gallup’s education division.

Leaving college with student-loan debt is a relatively recent occurrence. In 1989, only 17 percent of those in their 20s and early 30s had student debt. Student loan debt quadrupled last decade, passing the $1 trillion mark.

The massive run-up in debt coincided with a decrease in new business start-ups, according to the Census Bureau. Between 2008 and 2011, more businesses died annually than were created. And while that trend has reversed in recent years, big companies still dominate campus recruiting.

For the first time in the nation’s history, a majority of U.S. workers are employed at firms with 500-plus workers. In a day and age when students and parents are trying to calculate the return on investment of a bachelor’s degree, new graduates seem to find security in a job with an established company.

“If you go to career services and say ‘I’m going to start a company,’ they’ll push you toward a job because they worry you’ll show up in some statistic as unemployed,” said Andrew Yang.

Yang is the founder of Venture for America, a nonprofit organization that partners with startups in cities such as Baltimore and Detroit and pairs them with recent college graduates. For two years, the new graduates work for the companies in industries that vary from e-commerce to clean technology. The students earn a salary of around $38,000 a year and at some companies can even earn equity in the startup.

The 150 fellows accepted into the program each year, who fan out to 100 companies in a dozen cities, all begin with a five week bridge program, where they learn about product design, public speaking, and of course, entrepreneurship. Many of the fellows told me that this is where they first found their tribe—students like themselves who wanted to carve their own independent career path, instead of simply following everyone else into the jobs that already existed. According to Yang, “entrepreneurship is an isolating endeavor,” especially on college campuses.

Much like other young entrepreneurs, Venture for America fellows said they chose the program because they saw it as an insurance policy for their bachelor’s degree in a constantly evolving job market. About a half of VFA graduates remain in startups in some way after the program, either as a founder of their own or by working for one.

One of the fellows I met in Detroit, Tim Morris, a graduate from the University of Virginia, told me he picked architecture as a major because it intrigued him in high school. But like many students when they choose their major as a freshman, he had little idea what a full-time job in the field would really entail.

Then before his senior year at UVA he interned at an architecture firm in Atlanta. That’s when he first witnessed what daily life would look like after college. “The guy next to me was designing bathrooms for handicap accessibility, when I was designing parks and museums in college classes,” Morris said. “I wanted to do something with more impact.”

When he returned to UVA for his senior year, he looked into jobs at a nonprofit or for the federal government in Washington, but he worried that a career in a bureaucracy would lead to long stretches of unsatisfying work. That’s when he heard about Venture for America from a friend.

Instead of going to a place where recent college graduates clustered, he went to Detroit, where there was less competition from other recent graduates and where he felt he could stand out. With the help of VFA, he was placed in a startup that designs innovative workspaces. “You can have an ordinary job in a location like this, and it could suddenly become extraordinary,” he said.

Morris has already helped design a sculpture for a new public park in the city and is helping work on a new data center for Quicken Loans, which is headquartered in downtown Detroit. Morris committed to VFA for two years, and remains comfortable not knowing what will come next.

“I don’t have a five-year plan,” he said. “I want to see where this takes me next. So many people are focused on getting a job after graduation that they don’t want to wait to see if anything else is waiting for them around the bend.”

To many that job provides the needed paycheck to help pay down student loans. If the U.S. wants to its entrepreneurial economy to thrive, then higher education will need to become more affordable for more students interested in start-ups.