Nitesh Goel wasn’t sure how to turn his “accidental product” with a loyal following of 100,000 users into a real company. Aaron Feuer had 25 school districts using his tool but had few ideas about creating and scaling his business. Grant Hosford had built a programming game for his daughter and wanted to take it to market.

They were building vastly different tools. But all three looked to education technology accelerators for structure, guidance and resources to turn their products into functioning companies.

Joining Imagine K12 and Y Combinator “gave me opportunity to develop my product,” Goel tells EdSurge. “If I hadn't gone to an accelerator, I would have never raised the money I raised. They have connections with schools, they understand the US education system and the industry.”

The “accidental” product that Goel refined at Imagine K12 was Padlet, an online collaboration tool that allows anyone to share text, videos, images and links. It started as something he built as a college student that ended up being shared by friends and friends of friends. Since graduating from the accelerators in 2013, Padlet has raised $1.6 million and currently claims over four million users.

Like Goel, Feuer was also in college when he started working on the product that would become Panorama Education. Wanting to give students a greater voice, he and his friends developed a survey tool that allows educators to deliver and receive student feedback. After finishing Imagine K12 in 2014, Panorama now has users in over 6,500 schools, and boasts $16 million in venture funding from tech celebrities including Mark Zuckerberg.

Education technology accelerators, which typically run from three to four months, provide entrepreneurs with legal, IT and financial services along with mentorship, working space and access to educators, entrepreneurs, business partners and potential investors.

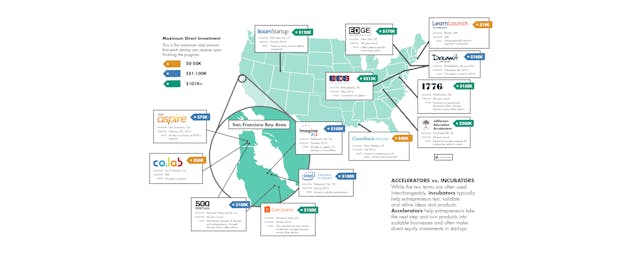

Unlike incubators—which offer similar aforementioned perks—accelerators typically invest anywhere between $18,000 to $200,000 in exchange for an equity stake. Their focus is on priming startups for fast growth—and sometimes fast money. Many accelerator programs conclude with a Demo Day pitch delivered in front of investors. By this time, entrepreneurs are expected to have built a sizable user base and feasible business plan as they prepare for the important—if not always the most enjoyable—step of fundraising.

Since Imagine K12 open its doors in 2011, over a dozen other edtech accelerators have sprouted around the world. And even within the niche of education technology, programs can target very specific kinds of entrepreneurs. Educational game developers like Hosford take to co.lab, based in Zynga’s headquarters in San Francisco. Camelback Ventures supports minority entrepreneurs. The Jefferson Education Accelerator works only with established companies looking to scale.

See full 18"x24" poster (pdf).

(The infographic above shows a list of the accelerator programs currently operating. Note that it includes only accelerators that invest in participating companies.)

The ballooning number of edtech accelerators, each of which can hatch upwards of a dozen startups every year—signals a dynamic investment environment, says Peter Yoon, a managing director at Berkery Noyes who advises education companies in merger and acquisition deals. “These programs increase startups’ chances of raising further investment and put them in a good position for an exit. Then, investors will be able to realize returns, which incentivizes them and others to keep investing in the sector.” It’s a “virtuous cycle,” he says.

The growth of accelerators has been accompanied by the surge in venture capital for edtech companies. In 2014, EdSurge tallied nearly $1.4 billion worth of deals in the US alone. During the first half of 2015, the figure already reached $1.1 billion.

The tremendous growth may come at a price, however. “The edtech marketplace is more crowded than it was a few years ago,” says Tim Brady, a co-founder of Imagine K12 who has reviewed several hundred applications. “It’s harder for entrepreneurs to come up with an original idea not found in the marketplace. In that sense, they have fewer chances.”

Venture capitalists believe market competition drives better ideas and innovations. In education, where many teacher and learners still use technology from decades past, that should be a welcome sign.