Summit Public Schools, which over the past four years has led the creation of the “Summit Learning Program” currently used by more than 380 schools around the U.S., said today that it will spin out that program into an independent nonprofit as of the 2019-2020 school year.

Diane Tavenner, who opened the first Summit school in 2003 in Redwood City, Calif., will continue to run the string of 11 physical Summit schools, located in California and Washington. But she will step out of the day-to-day management of the learning program once the separation takes place. Instead, Tavenner will serve as one of the founding board members of the still-to-be-named program. Other board members will include Priscilla Chan, who heads the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative (CZI), Peggy Alford, CZI’s chief financial officer and head of operations, and Alex Hernandez, formerly a partner at the Charter School Growth Fund and now Dean of the School of Continuing and Professional Studies at the University of Virginia.

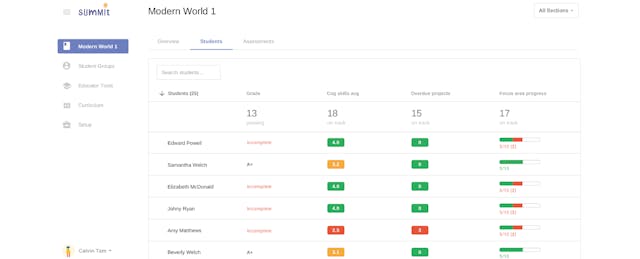

Meanwhile, CZI itself will continue to spearhead the team of approximately 50 engineers who are building and supporting the Summit software platform.

Tavenner described the move in a blog post on the Summit site. In a phone conversation with EdSurge, she emphasized that the software and support for schools that choose to adopt the Summit platform will continue to be free. “Our expectation is that there won’t be any change. It will look and feel the same” for the schools that use the platform, she said.

Most of the people currently building out the curriculum and support program at Summit will continue to do that work in the new nonprofit. That means at launch, the new program will have a team of more than 90 people including Summit's Chief Program Officer, Andy Goldin. The program is expected to continue to receive significant philanthropic support from CZI and other existing partners. The focus of the nonprofit will be familiar as well: expanding the program, developing curriculum and providing professional development and coaching for teachers in the schools that adopt the platform.

Even as many schools have embraced the Summit program with its emphasis on student "ownership" of their own work, growing the program has not been without controversy. In some school districts, notably including Connecticut and Kansas, parents have questioned whether the Summit program is a good “fit” for their communities. Other schools, such as some in the District of Columbia, have found that encouraging students to direct their own learning, as the Summit platform does, can be challenging.

Tavenner said that schools that use the Summit platform are able to weave their own curriculum into the materials provided by the learning program. But separating the 11 Summit schools from the leadership of the program may “send an even clearer message” that any of the 380 or so schools using the program can contribute content. And the schools that Tavenner will run will be just another group that uses the Summit learning materials. Or almost. “I think [our 11 schools] will wind up being the most demanding customers” of the Summit learning program, quipped Tavenner.

The brick-and-mortar Summit schools (including emerging middle schools) will consequently have more flexibility to build and strengthen those existing schools. And Tavenner and her team should also have more room to experiment with fresh ideas—starting with work on professional credentials and a teacher residency program. At Summit, “we are innovators—we incubate ideas well,” Tavenner said.

Tavenner dismissed any idea that she is looking to leave Summit. “I can’t imagine a better job than the one I have,” she said. “We have some exciting stuff in the works. There’s no shortage of ideas.”